course, and also Tumbleweed Connection). Twenty years ago I visited Coahoma County, Mississippi, where so many blues and R&B artists were born. I crossed the bridge to West Helena, Arkansas, and found myself in Levon territory, where Sonny Boy Williamson broadcast King Biscuit Time, and Helm had seen travelling minstrel shows. Just up the road was his birthplace, Marvell, and the place where his father farmed, Turkey Scratch. A few months later I got to talk to Tony Joe White about this; he rued the fact that gaudy casinos had changed much of this area irrevocably.

course, and also Tumbleweed Connection). Twenty years ago I visited Coahoma County, Mississippi, where so many blues and R&B artists were born. I crossed the bridge to West Helena, Arkansas, and found myself in Levon territory, where Sonny Boy Williamson broadcast King Biscuit Time, and Helm had seen travelling minstrel shows. Just up the road was his birthplace, Marvell, and the place where his father farmed, Turkey Scratch. A few months later I got to talk to Tony Joe White about this; he rued the fact that gaudy casinos had changed much of this area irrevocably. From Rip It Up, November 1993.

AS YOU DRIVE south out of Memphis down Highway 61, the trees and houses stop at the edge of the city limits. On either side of the narrow two-lane road, the horizon is almost bare, as far as the eye can see. This is the Delta, the land where the blues began.

Somehow this vast expanse of nothingness didn’t just produce cotton but an extraordinary number of blues singers, guitar players and songwriters. It feels timeless, and cut off from civilisation. But the music from this dirt table-top has had an effect all around the world.

Soon the small town of Tunica flashes by, a few gas pumps and motel signs. It was immortalised last year in ‘Tunica Motel’ by the great Southern songwriter Tony Joe White on his comeback album Closer to the Truth. “That was my fishin’ place, man,” he says, on the phone from Arkansas, west of the Mississippi. His deep drawl is so slow you could drive a tractor through his pauses.

“I went there and fished all the time with Duck Dunn, Booker T and the MGs’ bassplayer. It was a real laidback little place and still looks the same as it did years ago. But now, they’ve moved a gamblin’ riverboat into Tunica. There’s thousands of people coming into Tunica, gamblin’. It’s like the whole town is explodin’, so mah fishin’ hole is gone.”

“I went there and fished all the time with Duck Dunn, Booker T and the MGs’ bassplayer. It was a real laidback little place and still looks the same as it did years ago. But now, they’ve moved a gamblin’ riverboat into Tunica. There’s thousands of people coming into Tunica, gamblin’. It’s like the whole town is explodin’, so mah fishin’ hole is gone.”As the recent [1993] floods showed, the Mississippi is wont to break its banks occasionally. For centuries, before the levees were built and land cleared of its forests, swamps and bayous, the floods happened every year. And that made the topsoil of the Delta luxuriant, just right for cotton growing.

Writes Alan Lomax in The Land Where the Blues Began (Methuen, 1993):

“This treasure made its white owners not only rich but arrogant, although their main achievement had been to enslave and exploit the black labourers who actually cleared and tilled the land. The blacks had not only applied their inherited African agricultural skills to the development of the Delta, but had transformed remembered West African music into a new style, called the blues.”In 1942 Alan Lomax, a white folklorist, made a remarkable trip to the Delta that he’s just recalled in his equally remarkable memoir (all but unmentioned is John Work III, the black researcher who accompanied him). Ten years earlier, with his father, Lomax had discovered Leadbelly in a Louisiana prison. On this trip, recording blues singers on crude acetates for the Library of Congress, he met Robert Johnson’s mentor Son House and many others. Lomax’s memoir is not just an eloquent music history but a sensational tale of heartbreaking hardship, rollicking good humour and outrageous racism.

“You say we’ve got some talented niggers here in Tunica?” the sheriff asked Lomax in 1942.

“You’ve got the finest blues combination I’ve heard.”

“That so. Well, we’ll have to get um on the radio down in Clarksdale. What’re their names?”

“Well, Mister Son House is the...” I knew I’d made a mistake before the words were out of my mouth. The sheriff’s red face turned a beet colour.

“You called a nigger mister?!” he snapped. (Lomax)“I was raised on a cotton farm in Goodwill, Loosiana,” drawls Tony Joe White. “Goodwill was nothin’ but a church, a cotton gin and a pool hall. So every Saturday night everyone would go into Oak Grove, which is a little bigger. It had maybe 10 stores and a gas station and a Dairy Queen. So it was like going to a big town for us. We’d just go in and circle the Dairy Queen and wave at the girls and have a few cokes. It was laid back times.

“Most of the time we played at people’s houses. It was no band, it was just me and a rhythm guitar player. I used my foot on a coke box for something to drum. And people used to dance to it. At the time we was doin’ a lot of Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, Elvis Presley. This was before I started writing.”

In 1969, White had his biggest hit with ‘Polk Salad Annie’. He mixed country, blues, rock’n’roll and fishing to create swamp rock. His songs are shaggy dog stories about backwoods preachers, granny-eating gators, nasty sheriffs and their “volupchuss” underage daughters. On his new album Path of a Decent Groove, he tells the story of ‘Mojo Dollar’. “It’s about a guy we used to call Wild Man Swamps. And that guy, he went crazy and went down to live in the swamps of Loosiana.

“That song came pretty quick. Some of ‘em take a long time. I don’t just sit down and try to write. I have to wait until my guitar comes to me, or a word or a line. It’s like, I haven’t wrote a song for eight months. A lot of people just get up every day and say, today I’m gonna write for three hours...for me, that seems like impossible.

“Most of the time it’ll start with a guitar thing in mah mind. I’ll be fishin’ or playin’ golf and a little guitar will keep goin’ through my head. I’ll sit down with it and say, hey, I’m here. Show me what you’ve got. And once they get started I’ll put in hard hours with ‘em. I’ll build a little campfire outside my house, get me an acoustic guitar and sit out there with a few beers at night and work with it. But until that happens, I don’t mess with it.”

It’s as though there’s something in the water that produces so many songwriters in the area. Great regional radio helped too, the black-run WDIA out of Memphis with DJs like BB King and Rufus Thomas, and out of Nashville, the legendary R&B show of John R. “That’s all I ever listened to,” says White, “except Elvis.”

Here’s Muddy Waters, in Creem, 1977:

“All the great bluesmen lived near each other. No one was more than 25 miles apart all along the Delta. Robert Johnson wasn’t more than just 10 miles from me to the east and I still never met him – just seen him at a distance. I listened to them all down the road – Skip James, Charlie Patton, Bukka White, Kokomo Arnold. But Son House was my number one man, when he played slide he was the greatest.”Last year [1992] I had a spare day in Memphis, so I drove south in a rental car with Tennessee plates. Nothing but bland country stations and classic rock on the dial, but plenty of meaningful road signs on the way. About two hours south on 61 is Clarksdale, a quiet town of rundown brick buildings about the size of Levin. It seems about as exciting, but the small museum testifies to the town’s musical significance. Among those born in the area are Muddy Waters, Sam Cooke, Aretha’s father, John Lee Hooker, Ike Turner, Junior Parker, Bo Diddley...

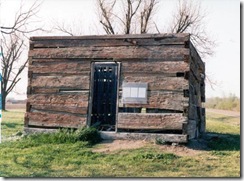

I took an unmarked road west and found myself accidentally on purpose on Stovall’s Road, which runs through Stovall’s plantation. I saw a tiny log cabin flash by, stopped, turned around, and there it was. Sitting without fanfare beside a back country road was the little shack in which Muddy Waters lived with his grandmother in the ‘30s. Here, in 1942, Waters took a break from ploughing cottonfields to play for Alan Lomax; this picture of Waters with Son Sims dates from around that time. Those Lomax recordings (recently reissued) lead to Waters’s career in Chicago. Follow the genealogical line through the Rolling Stones and it leads to Guns N’ Roses, and all that other big hair overblown blues on MTV.

I took an unmarked road west and found myself accidentally on purpose on Stovall’s Road, which runs through Stovall’s plantation. I saw a tiny log cabin flash by, stopped, turned around, and there it was. Sitting without fanfare beside a back country road was the little shack in which Muddy Waters lived with his grandmother in the ‘30s. Here, in 1942, Waters took a break from ploughing cottonfields to play for Alan Lomax; this picture of Waters with Son Sims dates from around that time. Those Lomax recordings (recently reissued) lead to Waters’s career in Chicago. Follow the genealogical line through the Rolling Stones and it leads to Guns N’ Roses, and all that other big hair overblown blues on MTV.Another conversation Lomax had in 1942:

“Little Robert [Johnson] learnt to play quicker than anybody we ever saw round this section,” said Son House. “He learnt from me and I learnt from an old fellow they call Lemon down in Clarksdale, and he was called Lemon because he had learnt all Blind Lemon’s pieces off the phonograph.”

I felt like shouting. Son House had laid out one of the mainlines in the royal lineage of America’s great guitar players – Blind Lemon Jefferson of Dallas to his double in Clarksdale to Son House to Robert Johnson.

“But isn’t there anybody alive who plays this style?” I asked.

“An old boy called Muddy Waters round Clarksdale, he learnt from me and Little Robert, and they say he getting to be a pretty fair player.”

The little shack was like a large, broken-down shoebox. In the 1990s it seemed so isolated it could have been in the Gobi desert. So imagine how exotic-Memphis, let alone Chicago, felt to Muddy Waters in the ‘30s. A few years ago, ZZ Top turned one of the shack’s wooden boards into a guitar to raise money for the Clarksdale blues museum. Now, a little sign asked that visitors didn’t take any toothpick sized bits as souvenirs. You sensed an international contingent of reverential fans had already made the pilgrimage: camera-happy Japanese, pedantic German scholars, list-making Brits, awe-struck New Zealanders. And all because they were moved by the same 12-bar magic.

The little shack was like a large, broken-down shoebox. In the 1990s it seemed so isolated it could have been in the Gobi desert. So imagine how exotic-Memphis, let alone Chicago, felt to Muddy Waters in the ‘30s. A few years ago, ZZ Top turned one of the shack’s wooden boards into a guitar to raise money for the Clarksdale blues museum. Now, a little sign asked that visitors didn’t take any toothpick sized bits as souvenirs. You sensed an international contingent of reverential fans had already made the pilgrimage: camera-happy Japanese, pedantic German scholars, list-making Brits, awe-struck New Zealanders. And all because they were moved by the same 12-bar magic.Robert Plant, from Q in 1990:

“On tour in Memphis, I rented a car and drove down to Mississippi, to Friars Point, as in the song. Very strange place, very African, very other-worldly. Sleepy, woodsmoke fires, big trees all around, burnt-out motels, deserted gas stations...”I headed down another narrow lane towards the levee. At a T-intersection was an old general store, its windows boarded up. Some black children played on the road outside three or four wooden houses. Above them loomed a water toward that said Friars Point. This was the place Robert Johnson sang about in ‘Travelling Riverside Blues’? “Just come on back to Friars Point, mama, and barrelhouse all night long.”

I couldn’t stop the engine, let alone get out of the car; the vehicle wasn’t just a goldfish bowl with central locking, but a way out. Not everyone was so lucky.

“Yessuh, I’s Mary Johnson. And Robert, he my baby son. But Little Robert, he’s dead.”Alan Lomax was just four years too late. Robert Plant and so many others, over 50. I headed across the Mississippi to West Helena, Arkansas, the home of Sonny Boy Williamson. In the little record store, the only albums that weren’t blues were by local hero Levon Helm of the Band.

“I love ole Levon’s music, man,” says Tony Joe. “But you know, I haven’t heard nothin’ from him in a long time. Since ole Clinton got to be president it’s like, Arkansas now, people talk about it all the time. I hope too many tourists don’t start coming up here. It’s a pretty quiet little place but I’m seein’ more and more campers nowadays. I’m so far back you almost need a four-wheel drive to get to my house. This ole farmhouse up in the Ozark mountains is about four hours from Memphis. There’s no television or anything, I’ve got a wood heater and a good fire going and I’ve got a front porch and a river – and that’s all you need.”

From such a backwater Tony Joe White and so many others have touched people of all cultures around the world. “My first hit was in Paris, France, before ‘Polk Salad Annie’,” he says. “It’d seem odd to me. I’d be sittin’ up there on stage, talkin’ just like I’m talkin’ to you. ‘Some of y’all never bin down South. I’m gonna tell you a little bit about it.’ I knew that they didn’t know what I was sayin’! But then, it was the feel of the music.”

No comments:

Post a Comment