17 August 2012

08 August 2012

Down the Road Apiece

Stanley Booth was the Zelig of rock’n’roll writing. A Southern hipster determined to become a serious writer, he was present in the Memphis studio when Otis Redding wrote ‘Dock of the Bay’, and he witnessed the Rolling Stones record ‘Brown Sugar’ in Alabama. He penned the liner notes to Dusty in Memphis, was a confidante of revered record producers Jerry Wexler and Jim Dickinson, and a friend and patron of street-sweeping Memphis bluesman Furry Lewis. That Booth came from the same small town in Georgia as Gram Parsons just confirms his knack of being in the right place at the right time.

It must have seemed that way when, after writing prescient, lyrical pieces on BB King and Elvis Presley for Esquire and Playboy in the 1960s, he was commissioned to write a book about going on the road with the Rolling Stones on their 1969 US tour.

The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones took Booth 15 years and almost cost him his life. The book became a critics’ favourite but was a box-office disappointment. It didn’t enable him to get on with his real ambition – to become a streetwise successor to William Faulkner – but aficionados of music writing consider it to be the one book in an over-published, undisciplined genre that approaches literature.

Booth was originally disdainful of white musicians trying to perform R&B; in a 1968 article he was scathing of a chaotic Janis Joplin performing alongside dignified Memphis soul legends. But he became fascinated by the Stones

The Stones’ 1969 tour is notorious for climaxing with Altamont, a free concert that became an apocalyptic nightmare. The tour also produced the live album Get Yer Ya Ya’s Out and the classic cinema verite documentary Gimme Shelter. The winter of 1969was one of discontent, of bad dope and bad vibes, with Nixon in th e White House, troops stuck in Vietnam, students protesting and generations clashing.

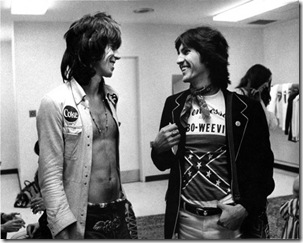

Booth’s book weaves through several stories simultaneously. There is the tour itself, with the writer having an access-all-areas pass and a rapport with Keith Richards that has professional benefits and lifestyle drawbacks. Almost subliminally, the Stones’ history is compellingly related using anecdotes from the participants. Booth describes the unlovable Brian Jones, his decline and inevitable demise. And he also tells his own story: a swift ascent to become a writer who then tumbles, like Icarus, from flying too close to the sun. The Altamont festival provides a chilling climax to the strands of his narrative. On stage beside the band, he stands transfixed but impotent as several Hell’s Angels viciously beat members of the crowd with pool cues.

The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones is written like a non-fiction novel. In Cold Blood was an influence, though Truman Capote’s own attempt at writing about the band’s 1972 tour stalled from writer’s block and a cultural disconnect. Booth was immediately on the Stones’ wavelength. His Southern accent, upbringing and contacts provided an entree: he could act as their regional interpreter. By appropriating R&B, rock’n’roll and country music, and adding their own Dartford Delta seasoning, the Rolling Stones produced their finest albums Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street, inventing a trans-Atlantic music steeped in popular culture and hedonism.

With an introduction by Greil Marcus and an afterword by the author, this handsome reissue by Canongate coincides with the Rolling Stones’ 50th anniversary. But it conveys their story far more evocatively than any sanctioned coffee-table book. To Booth’s annoyance, the 1984 US edition was melodramatically renamed Dance With the Devil. His own title – The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones – hints of James Fennimore Cooper. Booth had aspirations towards Raymond Chandler, and affectations to William Faulkner. But the one thing his original publisher did right was see the link to Edgar Allen Poe.

First published at Beattie’s Book Blog

03 August 2012

Waiting On a Friend

1. Making Baby Float

With minutes to spare, the IIML twitter alerts me to a concert taking place nearby at the grandly named New Zealand School of Music. The Spaces In Between is another collaboration between pianist and composer Norman Meehan, poet Bill Manhire and singer Hannah Griffin. It’s been a couple of years since I saw them at St Andrews on the Terrace, and in that time the careful treatments have gelled into compelling art songs, and Griffin’s performance has an added depth and assuredness. The poems given musical settings include David Mitchell’s witty ‘Aesthetics’ (I last saw Wellington’s leading Beat down the road nearby in John Street), Baxter’s ‘High Country Weather’ (appropriately spare), Manhire’s ‘Buddhist Rain’ and – with a gospel vocal trio - David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’. Meehan introduced Hone Tuwhare’s ‘To Elespie, Ian & their Holy Whanau’ as “curiously named”, which would be news to the peace-loving Prior family. But he has a lovely touch on the Steinway, his arrangements having a gentle humour, and at one point guest Colin Hemmingsen’s clarinet provides an oxymoron: a joyful lament. Keith Hill’s recent documentary on this troupe is called Persuading the Baby to Float.

2. Laus Tibi Domine

Art, Keith Richards once said, is just short for Arthur. Turning poetry into songs is a risky endeavour, the results are often so arch. Denis Glover apparently grumbled at Douglas Lilburn’s 1954 settings of his ‘Sings Harry’ poems, and it has to be said something more earthy would have been more suitable. Meehan’s success reminded me of Dave Dobbyn’s deeply moving treatment of James K Baxter’s ‘Song of the Years’, which opens, “When from my mother’s womb I came / Disputandum was my name …” It was a match made in heaven, so perhaps Dobbyn should look to updating ‘Sings Harry’: like Baxter, Glover is a kindred spirit. Charlotte Yates, who commissioned Dobbyn’s song for the Baxter album, wrote that his use of repetition “turned the somewhat lad-least-likely last line of the poem ‘Laus tibi, Domine!’ into an utterly joyful and triumphant outro.”

Art, Keith Richards once said, is just short for Arthur. Turning poetry into songs is a risky endeavour, the results are often so arch. Denis Glover apparently grumbled at Douglas Lilburn’s 1954 settings of his ‘Sings Harry’ poems, and it has to be said something more earthy would have been more suitable. Meehan’s success reminded me of Dave Dobbyn’s deeply moving treatment of James K Baxter’s ‘Song of the Years’, which opens, “When from my mother’s womb I came / Disputandum was my name …” It was a match made in heaven, so perhaps Dobbyn should look to updating ‘Sings Harry’: like Baxter, Glover is a kindred spirit. Charlotte Yates, who commissioned Dobbyn’s song for the Baxter album, wrote that his use of repetition “turned the somewhat lad-least-likely last line of the poem ‘Laus tibi, Domine!’ into an utterly joyful and triumphant outro.”

3. True Adventures

After a gap of 27 years, I’ve been re-reading the one book about rock music that approaches literature: Stanley Booth’s classic The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, about the 1969 US tour and so much more. First published in 1984, and recently reissued by Canongate, and I’m looking forward to reviewing it soon. It’s meant a revisit to the canon, especially Let it Bleed and Sticky Fingers (Exile got a workover at the time of its reissue in 2010). One of the standout moments is his observation, “There were no grownups among us.” I wish I could find the actual line again, but at a time when books fight to justify their space, this one has returned like a prodigal son.

4. Someone to protect

Which makes me think of a new earworm for the day, written circa 1973, released in 1981. Sax solo by Sonny Rollins.

5. Diversions

The IIML twitter also provides “A website that some folk might find handy.”