I recently interviewed Greil Marcus about his book The History of Rock’n’Roll in Ten Songs (it can be heard at Radio New Zealand's website here). With the imminent release of The Complete Basement Tapes – six CDs, well over 100 songs that Dylan wrote while woodshedding with the Band in 1967 – I had to ask about them. I wondered whether – now that the sessions were finally seeing daylight – this would change the public’s fascination with them. Marcus’s response shows that his fascination with the Basement Tapes hasn’t dimmed since he wrote a whole book on the sessions, Invisible Republic, in 1997:

I recently interviewed Greil Marcus about his book The History of Rock’n’Roll in Ten Songs (it can be heard at Radio New Zealand's website here). With the imminent release of The Complete Basement Tapes – six CDs, well over 100 songs that Dylan wrote while woodshedding with the Band in 1967 – I had to ask about them. I wondered whether – now that the sessions were finally seeing daylight – this would change the public’s fascination with them. Marcus’s response shows that his fascination with the Basement Tapes hasn’t dimmed since he wrote a whole book on the sessions, Invisible Republic, in 1997: You know there’s a lot of material – there’s 30 something songs – that have never been heard before, that haven’t been bootlegged or leaked out, song by song, on Dylan’s own Bootleg Series. Certainly there’s stuff I never heard before. And what’s fascinating about it, in the context of the whole set – which I think is going to start this conversation all over again – is you know how down-to-earth and ordinary and ah, work-like a lot of the stuff is.2. His Back Pages

The [phrase] that leapt to mind when I was listening to the stuff that I hadn’t heard before was “song mining”. These people are digging into what look like songs but they aren’t really. And you just keep digging to see if you find something in there that will explain itself, that will say, ‘No! No! Go in this direction, not that direction’ Really digging in the ground, and finding a root, and grabbing onto that root and thinking, ‘Well this root must lead somewhere, and maybe you find where it leads and maybe you don’t. These are people mining for songs.

And I think that when people listen to all of this material – and its 140 tracks – they’re going to be fascinated by the way that fragments and cover versions of songs that weren’t that interesting to begin with, and experiments that really don’t go anywhere, surround these songs that seem like gifts from the Gods. It’s going to make the whole question of creation, of creativity and writing, and playing and improvising, even more mysterious than it already is.

In some ways the mystique of the Basement Tapes I think is going to be washed away – replaced by the spectre of a bunch of people getting together every day to fool around – in a clubhouse, in a kind of boy’s club.

On the other hand you can say, Well okay, but where did this stuff come from. My God: ‘Tears of Rage’, ‘I Shall Be Released’, ‘This Wheel’s on Fire’ … did some visitation come down and strike these people with lightning, and then go away and leave them to play with ordinary hands – as they weren’t doing for a few weeks?

I don’t know. But I love the way there is stuff here that is mediocre, that is second rate, and stuff that seems like junk – it sounds bad and it’s very hard to hear – and has flashes in it that are as strong and as disturbing as anything in the formal masterpieces that these sessions produced.

So I think you can tell by the way I’m answering that I don’t know. That I don’t know how to answer your question. That it’s as if you have to learn how to start listening to the stuff as if you’ve never heard it before. And see what story it tells.

At last, a one-stop shop of Greil Marcus’s archives: articles, interviews and reviews, regularly updated. It was a very smart idea to compile a series of links to all the songs in his “Treasure Island” of essential discs Marcus added to Stranded, the 1979 anthology he edited in which music writers wrote about their “desert island disc”. (The essays by Lester Bangs on Astral Weeks, and M Marks on It’s Too Late to Stop Now are unsurpassed. Bangs’s masterpiece aside, one of the best reviews of Astral Weeks I ever heard was from an older woman who just said, “You breathe in, you breathe out, you breathe in, you breathe out.”)

3. Writer’s block

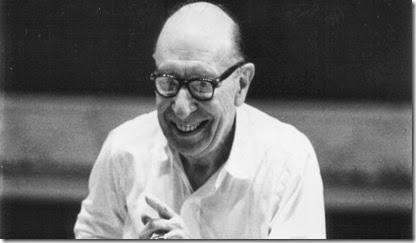

Of the six artists featured in Marcus’s 1975 classic Mystery Train (Harmonica Frank, Robert Johnson, the Band, Sly Stone, Randy Newman and Elvis Presley) only Newman’s career seems to have continue, rather than ended with pathos. Still, the exposure didn’t come without a cost to his productivity. In 1983 – I think in San Francisco’s BAM magazine – Newman said:

When I’m writing songs, the minutes are like hours – I sit there with nothing, just a big picture of Greil Marcus in my mind hanging over the piano as I think, ‘Ah, I don’t think this guy is gonna like this one, because I’m doing the same stuff he criticised me for before.Marcus’s response? “You know, anybody who reads something I’ve written and comes back and tells me something about it that I didn’t know – that’s a valuable a reader as I can ever hope to have. And that’s happened with musicians and people who aren’t musicians. I really can't talk about other people’s reactions to my work, at least not positive reactions, it just comes off as self-congratulation. I’m lucky that I’ve been able to write, to find people to publish me, and to find people who read me. So that’s all I can say.”

4. Country gentlemen mystique

Speaking of the Band, I stumbled upon these 1969 reviews from the Village Voice of the Band live at the Fillmore, and of their second album. The writer, Johanna Schier, has a charming straightforward style, with a wry wit, a talent for an apt metaphor – and musical insights. (Though she describes Robbie Robertson on stage as “sweetly bashful”, she also hears Smokey Robinson in the chorus of ‘I Shall Be Released’). Schier soon befriended Janis Joplin, and with her future husband John Hall wrote ‘Holy Moon’, the b-side of ‘Me and Bobby McGee’. The pair then founded the group Orleans.

5. Ballad of a Teenage Queen

We have heard a lot from Jerry Lee Lewis over the years, especially about rock’n’roll and the Devil, but little from his child bride, Myra. At last, she breaks her silence. “They were looking for a place to stick the knife into rock & roll. And Jerry gave it to them—well, I did, I opened my mouth.”

We have heard a lot from Jerry Lee Lewis over the years, especially about rock’n’roll and the Devil, but little from his child bride, Myra. At last, she breaks her silence. “They were looking for a place to stick the knife into rock & roll. And Jerry gave it to them—well, I did, I opened my mouth.”6. Click track

From David Hepworth, a link to a batch of classic Motown hits with the vocals removed. I know, that seems criminal, but it is so illuminating to be able to concentrate on the Funk Brothers.

7. Down the avenue again

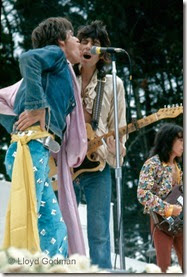

Van Morrison’s paranoia about YouTube seems to have dissipated. Three extraordinary, lengthy clips have recently been added to the site, without legal intervention thus far. The legendary It’s Too Late to Stop Now 1973 shows at London’s Rainbow were broadcast by TVNZ later in the 1970s on The Grunt Machine and talked about for years; a high-def version has been up for a while. Now, two other full-length concerts from the same period are online. At Winterland in February 1974, in B&W, the band is his usual combo from “Street Choir” period – also featured at the Rainbow, but lacking the string quartet. With a completely different – and integrated – band, but several of the same songs, he can be seen in full colour at the Orphanage, San Francisco in July 1974 (note the presence of Tom Donahue, the deep-throated influence on all FM rock jocks). Both feature Morrison’s ‘Caravan’ can-can schtick. Perhaps best of all is this 10-minute clip from the Fillmore East in September 1970, introduced by Bill Graham: maybe the earliest filmed version of his ‘Cyprus Avenue’ tease. As a taster to the Winterland gig, here he is covering Dylan’s ‘Just Like a Woman’.

8. Funky, funny and fun

More back pages: here is how the Victoria University of Wellington’s student newspaper Salient reviewed Abbey Road in 1969. Mike Bergin described the medley of songs on side two as “a mess”, whereas that was the only passage Nik Cohn liked in his New York Times review. But Bergin showed a lot of promise in this and other reviews; sadly, he died not long afterwards in a car accident.

9. Back to the Island

In July, Glenn Jowitt – one of New Zealand’s greatest photographers – died suddenly. He was mourned in Auckland by about 400 of his closest friends in a moving, multi-cultural ceremony. The NZ Herald asked me to write an obituary.

10. Take the Coltrane

A crucial influence on Glenn was the expatriate New York photographer Larence Shustak, who taught him at Ilam School of Fine Arts in Christchurch in the mid-1970s. Glenn was a dedicated music fan and an enthusiastic guitarist (in the 70s he even looked like his hero, Gram Parsons). A connection he had with Shustak that I never knew until researching for the obituary: in the 1950s Shustak took many compelling shots of New York jazz musicians.

11. A little bit frightening

Musical racism 101: ‘Kung Fu Fighting’, or how to express the whole of Asia in just nine notes. No, not the lyrics – which are bad enough – the influence of the arrangement has been even more pervasive, reports NPR.