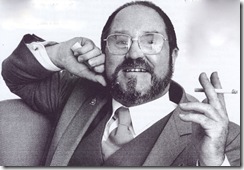

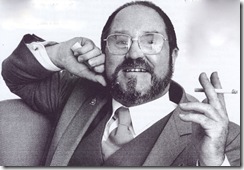

Recently I was talking with someone who hadn't heard of Phil Warren, the groundbreaking Auckland promoter who died early in 2002. My friend was too young for NZBC-TV's Studio One and then overseas for Warren's stint in local politics. But with the perennial constipation in Auckland urban planning, always exacerbated by central government, it's timely to remember that a local politician could be visionary, successful - and good fun. This obit first ran in the NZ Listener on 9 February 2002.

Phil Warren, Impresario

Phil Warren, Impresario

Irrepressible, imaginative, energetic, brash, provocative, entertaining, Phil Warren had all the ingredients to be a classic demagogue. Instead he used his talents to further his passions: entertainment and the region of Auckland. The two connected often; he believed show business and politics were natural bedfellows. Both require the gift of the gab – and a natural charisma to encourage people to get out and vote for you. He knew the old gag – “politics is show business in drag” – and once put it to use when he booked Diamond Lil for a Labour Party conference. Besides all the acts he booked, all the local body meetings he chaired, in the early 1970s he altered the social fabric of New Zealand when he acted like a one-man lobbyist to change archaic laws that prevented licensed drinking after 10 o’clock. “I always vote for Phil,” an Auckland friend once said. “He’s the only politician who believes people should be allowed to go out at night.”

New Zealand after hours wasn’t closed for Warren when he was a teenager in the 1950s: it was an opportunity. He got his start in the music business at 14, working at the Beggs music store. As soon as he left school, he was on the road, selling instruments. Inspired by his jazz trumpeter uncle Jim, he had learnt the piano and played the drums, but realised very early on that other people had more talent – and his was for guiding and presenting them. By the age of 18, he had his own record label, importing R&B and jazz from small labels in New York and Chicago, dealing with dodgy characters in the murky days of music who nevertheless kept their word.

An album of the corny English musical Salad Days paid many of the bills and he started signing local acts to his label, Prestige. In 1958 a young man from Wanganui changed everything: Johnny Devlin was New Zealand’s Elvis, a genuine phenomenon helped along with stunts worthy of Colonel Parker himself. Warren organised “mini-riots” for the media that almost turned into the real thing; Devlin’s stage clothing was loosely stitched so it fell apart when grabbed by fans. ‘Lawdy Miss Clawdy’ sold nearly 100,000 copies and Devlin’s tours were massively successful. This was indeed the Devil’s music: his band was called the Devils, and one tour featured a female impersonator. There were questions in parliament – politician Mabel Howard jumped on the bandwagon – and to deflect controversy Warren arranged a photo call with visiting evangelist Billy Graham.

An empire worthy of Epstein followed: a talent agency and a touring circuit of coffee lounges and dancehalls: the Crystal Palace, Mojo’s, the Montmartre, Teenarama. Their attractions were revolutionary: espresso coffee, coloured lights, mirror balls. Later on, you knocked three times to enter the Crypt, a place that pushed licensing laws to the limit.

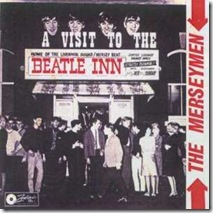

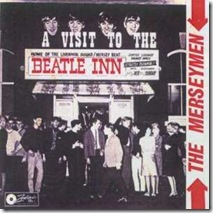

He was always quick to see a gap. When the NZBS banned Chubby Checker’s “The Twist”, Warren recorded a version by Herma Keil and the Keil Isles and had a bigger hit. When the Beatles were on their way, he opened the Beatle Inn in downtown Auckland. Open Wednesdays to Sundays, including lunchtimes, it was R18: no one over 18 was allowed in. The resident band was the Merseymen, playing an all-Liverpool dance card; the drummer was called Jet Rink. “He’d go into the phone box, take off his cape and turn into Dylan Taite,” Warren recalled in October. “A good drummer, a good entertainer – and about as good a singer as me.” Warren claimed he registered the Beatles’ name locally before they had done it worldwide, and bundled together agency photos into an album called The Beatles Book. “Hardly original, but we sold about 6000 at 2/6 each.”

He was always quick to see a gap. When the NZBS banned Chubby Checker’s “The Twist”, Warren recorded a version by Herma Keil and the Keil Isles and had a bigger hit. When the Beatles were on their way, he opened the Beatle Inn in downtown Auckland. Open Wednesdays to Sundays, including lunchtimes, it was R18: no one over 18 was allowed in. The resident band was the Merseymen, playing an all-Liverpool dance card; the drummer was called Jet Rink. “He’d go into the phone box, take off his cape and turn into Dylan Taite,” Warren recalled in October. “A good drummer, a good entertainer – and about as good a singer as me.” Warren claimed he registered the Beatles’ name locally before they had done it worldwide, and bundled together agency photos into an album called The Beatles Book. “Hardly original, but we sold about 6000 at 2/6 each.”

Acts that appeared on Kevan Moore’s seminal TV music shows Let’s Go and C’mon weren’t exclusively booked through Warren’s agency, but he was a dominant talent spotter and “synergies” did exist for his clubs and tours. He made sure stars such as Mr Lee Grant or the Chicks played for two audiences: teenagers on the C’mon tours, with cabaret shows for their parents.

In the days of one-channel television, Warren’s appearances on the talent shows Studio One and New Faces gave him a household presence: his role as a judge was to play the “big bad heavy”. At home we could be blunt, picky and outrageous, but Warren said these things out loud. Though his own grooming was curious – trimmed beard topped with a comb-over – beware the contender wearing a lurex dress, a home-knitted cardy or unshined shoes.

He toured Johnny Cash as early as 1959, and later overseas acts such as the Hollies and the Rolling Stones. Mick Jagger was “one of the smartest businessmen” he ever met, running the band “like the CEO of a high-tech profitable business operation.” He almost came a cropper booking Robin Gibb for the Redwood 70 festival. Later, Rod Stewart’s Faces trashed the Warren family grand piano on stage – and received a bill for their vandalism.

The Hollies were a catalyst for his next phase, the shift into politics. One of the first acts to play the speedway stadium Western Springs, Warren had booked the Hollies at the cheaper rate for an indoor venue. Seeing the large outdoor crowd, the band refused to go on stage until they had renegotiated their deal. They went on, but the show began Warren’s disgust at the appalling facilities of Western Springs. He had many public arguments with the council, which took his fees for the venue, but didn’t put any money back into the fences or the toilets. “The mayor of the day was dear old Robbie, and he said to me ‘There’s no sense being outside the tent. You must come inside the tent’ – though he didn’t say it as delicately as that.”

His career in local politics – Auckland City councillor, deputy mayor, acting mayor, chairman of the Auckland Regional Council, board member or patron of forums, committees, arts bodies and countless societies – closed the era of Phil Warren as King of Clubland. In the 1970s, the clubs had become post-music hall dens of innuendo with names like Dirty Dicks, Bimbos, Adam’s Apple and Doodles – and acts such as Dave Allen and Dick Emery. They were awful, but we liked them – and they kept Warren’s gold Rolls-Royce on the road. (It was called José, as it was bought from profits of a José Feliciano tour.) In the mid-70s the “one-in-a-million chance” of five shows going bad at once lead to Warren putting his touring company into voluntary liquidation. The days of Barbara Windsor, Patrick Cargill, Tony Christie and the Black and White Minstrel Show making box-office magic were over, but Warren was proud of the way he handled it: he sold his family home and traded his way back so that “100 percent of creditors received 90 cents in the dollar”.

My first sighting of Warren was in his Rolls, sitting outside the Six Month Club – he had sub-let his Ace of Clubs venue just before it was demolished to make way for the Aotea Centre. It was 1985 and he was waiting for Rip It Up's 100th issue party to start, and he looked exactly the way an impresario should look.

Three months ago, in October 2001, he bounded into Radio New Zealand’s Auckland studio for the Saturday morning programme with John Campbell. He had leapt at the offer to play his favourite New Zealand music, and knew why he had been asked. His selections went “way, way back, beyond Dave Dobbyn, the Finn boys and Bic Runga” to his friends the Keil Isles, Vince Callaher and Lou & Simon; he name-checked the composers Ruru Karaitiana, Alfred Hill, Peter Cape, John Hanlon. He was outrageous and passionate, an old trouper stealing the show. He even had a CD to plug – his nostalgia collection Play It Again, Phil – and a few days later at Apra's 75th anniversary party Warren admitted he had deliberately prevented the host getting a word in edgeways.

As I walked to work last week through the Auckland that Warren helped turn into a music centre, past the venues now pulled down (he supported the destruction of His Majesty’s, a “rat-infested dump”) or currently operating as dance clubs, it struck me that his last campaign combined his two passions, and went back to the time the Hollies had lead him to politics. Battling Mobil Oil to lower the sulphur content in diesel, he had left Aucklanders a lasting legacy: the air that we breathe.

Flags flew at half-mast over Harbour Bridge the day Warren took his final curtain. At the funeral service, Helen Clark called him a “human dynamo”, Howard Morrison declared he was “the boss” of entertainment, and Dean John Rymer recalled the lurid underwear Warren wore to the gym: “He was showbiz right down to the skin.”

From this distance it’s difficult to comprehend the moral panic associated with early rock’n’roll in New Zealand. It is no exaggeration to say that just the sight of a greaser with winklepickers would make mothers cover their toddlers in their prams. Tanked dads with RSA badges on their lapels would accusingly spit out “bodgie” with the vehemence of the Jew-hating Nazis they had just fought against. Underage drinking and teenage sex are comparatively condoned now with RTD alco-pops and STDs rampant, but in the mid-1950s they so outraged society there was a Parliamentary commission examining youth morals.

From this distance it’s difficult to comprehend the moral panic associated with early rock’n’roll in New Zealand. It is no exaggeration to say that just the sight of a greaser with winklepickers would make mothers cover their toddlers in their prams. Tanked dads with RSA badges on their lapels would accusingly spit out “bodgie” with the vehemence of the Jew-hating Nazis they had just fought against. Underage drinking and teenage sex are comparatively condoned now with RTD alco-pops and STDs rampant, but in the mid-1950s they so outraged society there was a Parliamentary commission examining youth morals.