If you’re looking for the real Elvis, you’ve come to the right place.

LAST TRAIN TO MEMPHIS: The Rise of Elvis Presley, by Peter Guralnick (Little, Brown).

What follows makes a heartbreaking conclusion to Last Train to Memphis, the first volume of Peter Guralnick’s two-part biography of Elvis Presley. While fans keep a vigil at the gates of Graceland, in the kitchen, Elvis’s cousins and cronies get drunk. In the music room, Elvis sobs and keeps hugging and kissing his mother’s body in its silver casket. A doctor administers a sedative so Elvis can sleep before the funeral, for which Hollywood stars fly in from the coast. Elvis has to be helped into the church; he sobs as his mother’s favourite gospel group sings hymns. At the cemetery he leans over the coffin and cries out, “Goodbye, darling, goodbye.” Four friends drag him to his limo, where he declares, “Oh God, everything I have is gone.”

That night, he tells his childhood sweetheart that his life is getting out of control. He is surrounded by new friends, they depend on him now, he can’t walk away. “I’m in too far to get out.” A few weeks later, Private Elvis Presley, serial number 53 310 761, is on a troopship to Germany. The rollercoaster ride of the past three years is over. Elvis is 23.

Guralnick is the leading historian of American roots music: blues, country, R&B and soul. Unlike many pop writers, who rely on hyperbole or ego, he writes with the sober eye of a musicologist and the ear of a true fan. As a consequence, his prose sings with authenticity. And his books – among them Lost Highway, Feel Like Going Home and Sweet Soul Music – have always been in print, unlike most pop books.

Since then, the running joke that “Elvis is Alive” has only shifted the myth away from the music. And no one could have predicted last year’s marriage between Michael Jackson and Lisa-Marie Presley. That’s what happens when you start reading the tabloids. When it comes to Elvis, it’s best to keep a sense of humour and perspective -and return to the primary sources.

Guralnick has compiled his biography like a detective, interviewing first-hand observers and comparing their stories to sort out the accurate from the apocryphal. Contemporary news reports and previously published accounts are quoted when the participants are no longer available (ie, dead). Guralnick also consults archive tapes of Presley interviews and recording sessions, TV shows and concert film footage.

The closing scenes described above may sound melodramatic, but Guralnick’s fastidious research makes them utterly credible. The difference is in his attitude -he knows that what drives musicians is often not a quest for stardom, but a sense of vocation. The biography is not hagiography. He delivers the evidence, not a verdict, and avoids speculation, sensationalism and pop psychology.

The story is familiar, but never before has it been told in such evocative detail (Guralnick fills in the facts behind Greil Marcus’s intellectual flights of fancy in Mystery Train). It takes off with Presley’s metamorphosis from misanthrope to musician. The moment in which Elvis, Scotty and Bill discover the sound – by countrifying “That’s All Right [Mama]” – is pure magic. Guralnick’s style is almost novelistic, but scrupulously sourced.

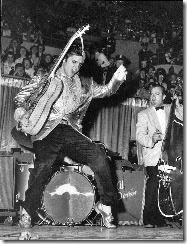

Certain themes recur: Presley’s awareness of his image (every outfit is lovingly described) and of every nuance of his performance – hiccup, hip shake or “affable sneer”. Meanwhile, dark clouds loom overhead: the growing Memphis mafia of hangers-on, the increasing crassness of Colonel Parker’s management hustle, the increasing mail from Presley’s draft board – while his mother sits at home drinking beer, missing her baby.

First published in the NZ Listener, 28 January 1995. If he is alive, Elvis is 80 today. I was going to link to his version of Dylan’s ‘Tomorrow’s a Long Time’ but this is a lot more fun …