1. Sliver of hope

New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd compares this gloomy era in journalism to the film Sunset Boulevard, rewriting the famous quote of aging actress Norma Desmond: “Papers are still big. It’s the screens that got small.” She asks Phil Bronstein, editor of the troubled San Francisco Chronicle, to take her on a “justify your existence” tour. Bronstein drives her past the journalists’ bar, now empty, the police headquarters where they uncovered corruption, the SF General Hospital, once teeming with Aids patients. In magazines, when the circulation department receives its returns marked “Subscriber deceased: please cancel,” it’s a stark reminder that one’s readership is aging. But this is now a good thing, reasons Bronstein:

New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd compares this gloomy era in journalism to the film Sunset Boulevard, rewriting the famous quote of aging actress Norma Desmond: “Papers are still big. It’s the screens that got small.” She asks Phil Bronstein, editor of the troubled San Francisco Chronicle, to take her on a “justify your existence” tour. Bronstein drives her past the journalists’ bar, now empty, the police headquarters where they uncovered corruption, the SF General Hospital, once teeming with Aids patients. In magazines, when the circulation department receives its returns marked “Subscriber deceased: please cancel,” it’s a stark reminder that one’s readership is aging. But this is now a good thing, reasons Bronstein:

His tour ended with cold comfort, as he observed that longer life expectancies may keep us on life support. “For people who still love print, who like to hold it, feel it, rustle it, tear stuff out, do their I. F. Stone thing, it’s important to remember that people are living longer,” he said. “That’s the most hopeful thing you can say about print journalism, that old people are living longer.”

The reference to crusading journalist I.F. Stone (pictured above) was heartening - the Seymour Hersh of his day, for years he ran his own I.F. Stone's Weekly - and intriguing. I don't think he was a relative of Bronstein's short-term wife, Sharon Stone.

2. Cold beer, hot type

There are few books written about New Zealand novelists, but even fewer about its journalists. After the Fireworks is both, a biography of novelist and Auckland Star leader writer David Ballantyne, who died in 1986. It’s an evocative portrait of the loneliness of a writer in a hostile culture, diverted by the hard-drinking, hard-bitten but strongly bonded world of newspapermen in the 1940s and 1950s. Ballantyne’s first novel The Cunninghams was written when he was just 23, in 1947, and published in the US; it would be another 15 years before he published another.

There are few books written about New Zealand novelists, but even fewer about its journalists. After the Fireworks is both, a biography of novelist and Auckland Star leader writer David Ballantyne, who died in 1986. It’s an evocative portrait of the loneliness of a writer in a hostile culture, diverted by the hard-drinking, hard-bitten but strongly bonded world of newspapermen in the 1940s and 1950s. Ballantyne’s first novel The Cunninghams was written when he was just 23, in 1947, and published in the US; it would be another 15 years before he published another.

Long sessions at the Occidental in Vulcan Lane were part of the reason, but he managed to get off the bottle in 1973 and produce a late flurry of work. After the Fireworks captures the smoky newsrooms, the pride and wisdom of the long-serving reporters and sub-editors, the daily post-deadline binges, the hidden subcultures such as the rundown flat at 301 Willis Street, Wellington, where journalists, poets, novelists (and even Douglas Lilburn) would come and go, knowing they could get a beer after six o’clock closing. Under the circumstances, the Aucklanders’ productivity is extraordinary:

“… visits to Willis Street were sporadic and impulsive excursions, usually involving drinking in Auckland on a Friday after work, catching the overnight train to Wellington, drinking at various Wellington watering-holes … partying on at 301, then catching the Sunday night train back to Auckland in time for work at the Star on Monday morning.”

The biography was written by Ballantyne’s friend Bryan Reid; the pair started at the Star on the same day in 1943. The book slipped under my radar when it came out in 2004 but – like Ballantyne’s best, Sydney Bridge Upside Down, from 1968 – is recommended.

3. Quality of Mercer

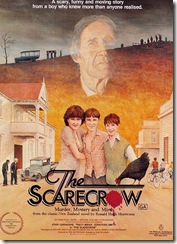

The Dominion Post runs the country’s best obituaries, but didn't quite get the tone right with a recent tribute to the former Dominion editor, Jack Kelleher. Portraying him as a cardigan-wearing conservative – and concentrating on the brief tabloid folly of Rupert Murdoch – doesn’t tell the whole story. A quick glance at Kelleher's journalism suggests he moved in a broad circle. His ghost-writing of forensic pathologist PP Lynch’s memoir No Remedy For Death is mentioned; erudite, stubborn, patrician, Lynch did not suffer fools. Kelleher could work the public bar as well: he was close enough to the “hermit of Hawera,” novelist Ronald Hugh Morrieson, to be a key source for Julia Millen’s biography. His history of Upper Hutt reveals a rapport with Wellington’s hippest post-war bandleader, Fred Gore. And his sensitive obituary of Ruru Karaitiana in 1970 – the only one the ‘Blue Smoke’ songwriter received – indicates a newspaperman who never stopped working his beat (in this case, Wellington’s inner-city music precinct of the late 1940s: Mercer, Willis, Manners and Bond streets). Maybe not Clark Kent, but a very effective mild-mannered reporter.

The Dominion Post runs the country’s best obituaries, but didn't quite get the tone right with a recent tribute to the former Dominion editor, Jack Kelleher. Portraying him as a cardigan-wearing conservative – and concentrating on the brief tabloid folly of Rupert Murdoch – doesn’t tell the whole story. A quick glance at Kelleher's journalism suggests he moved in a broad circle. His ghost-writing of forensic pathologist PP Lynch’s memoir No Remedy For Death is mentioned; erudite, stubborn, patrician, Lynch did not suffer fools. Kelleher could work the public bar as well: he was close enough to the “hermit of Hawera,” novelist Ronald Hugh Morrieson, to be a key source for Julia Millen’s biography. His history of Upper Hutt reveals a rapport with Wellington’s hippest post-war bandleader, Fred Gore. And his sensitive obituary of Ruru Karaitiana in 1970 – the only one the ‘Blue Smoke’ songwriter received – indicates a newspaperman who never stopped working his beat (in this case, Wellington’s inner-city music precinct of the late 1940s: Mercer, Willis, Manners and Bond streets). Maybe not Clark Kent, but a very effective mild-mannered reporter.

4. A comic sign of health

The same week of Kelleher's death, I found Ballantyne's biography in a small town sale bin. Both reminded me of Julia Millen's biography of Morrieson, from 1996, which also hasn't reached the audience it deserves. The pair had quite a bit in common: their era, their profession, their obscurity, and their alcoholism. Unlike Ballantyne, Morrieson didn't leave a swag of diaries, letters and manuscripts, which made Millen's task more difficult. But by weaving in anecdotes from his fiction, and putting in plenty of leg work, she captured his drive and his demons, in that closed Taranaki world.

“Herbert had told me on the quiet that he reckoned Uncle Athol had got his teeth from Mr Dabney, the undertaker.” (The Scarecrow)

“What is this thing called gothic?” asked Morrieson, after a rare literary review during his lifetime. Just months before Morrieson died - yes, “another one of those buggers” who only became famous afterwards - Robin Dudding published two “appreciations” in Landfall 98 (June, 1971). Morrieson's champions were Frank Sargeson and CK Stead, and the issue had a cover design by Pat Hanly. Sargeson wrote:

“What is this thing called gothic?” asked Morrieson, after a rare literary review during his lifetime. Just months before Morrieson died - yes, “another one of those buggers” who only became famous afterwards - Robin Dudding published two “appreciations” in Landfall 98 (June, 1971). Morrieson's champions were Frank Sargeson and CK Stead, and the issue had a cover design by Pat Hanly. Sargeson wrote:

We hear sometimes of somebody who intends a march on Parliament in order to emphasise some fact of human nature or human society. It would be a comic sign of health in the community (not to mention an immense compliment to Mr Morrieson, and his skill in revealing to us much about the inner nature of human life in our country), if Parliament were to march upon him and his home town.