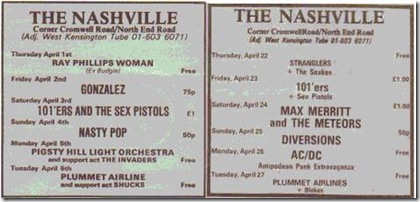

Thirty-three years ago today I was on a bus going through Wellington when I spotted the Evening Post’s billboard for that night’s paper. THE KING IS DEAD, it said in a huge typeface. Below, in smaller letters: ELVIS PRESLEY R.I.P. He was 42. This piece on Elvis’s oft-maligned 1960s recordings was first published in Real Groove in 1993.

ELVIS wasn’t everywhere in the mid-60s. But I would come across him some Saturday afternoons, when my brother would dub me on his bike, with my sister and the kids next door trailing behind, down to the Deluxe theatre in Lower Hutt.

Before we settled in to watch Carry on Constable, Robin Hood or It’s a Mad Mad Mad World, there’d be some shorts: usually, a widescreen trailer for Lawrence of Arabia, and some scenes from the latest Elvis flick.

There he would be, guitar in hand, singing along to a hidden orchestra; on the back of a truck, on a boat, a horse, or with a hula hoop around his hips. He seemed from another age, and was definitely uncool. But that wasn’t the reason we didn’t see the movies: we weren’t allowed to, just as our parents didn’t let us see the movies of our favourites, the even more subversive Beatles.

“Elvis is dead?” said John Lennon in 1977. “He died when he went into the army.” That’s the accepted line, the shorthand version of rock’n’roll history. The explosion of pop music in the 60s has meant the music Elvis made in that period was irrelevant, his output a mere footnote that says he wallowed in bland material and mediocre movies until his phoenix-like comeback at the end of the decade.

Of course it’s not as simple as that. But now, with Elvis being not merely the king of rock’n’roll but an icon - a symbol of faith or farce depending on your point of view - a more complex synopsis has been difficult to convey. Finally, with the release of Elvis: From Nashville to Memphis, the Essential 60s Masters, the big picture can be seen, by both blinkered acolytes or sneering Goldmanites. Over 130 tracks, limited to his non-movie, non-gospel studio recordings, we can hear the development of his music and understand its diversity and inconsistencies.

Of course it’s not as simple as that. But now, with Elvis being not merely the king of rock’n’roll but an icon - a symbol of faith or farce depending on your point of view - a more complex synopsis has been difficult to convey. Finally, with the release of Elvis: From Nashville to Memphis, the Essential 60s Masters, the big picture can be seen, by both blinkered acolytes or sneering Goldmanites. Over 130 tracks, limited to his non-movie, non-gospel studio recordings, we can hear the development of his music and understand its diversity and inconsistencies.

The surprise of the five-CD set is not how much good material there is, nor how much dreck. It is what the chronological programming tells us. When the chips were down, Elvis could rise to the challenge. When the material was worthy of his talents, Elvis responded. Most significantly, the magnificent Memphis sessions in January 1969 were not a happy accident, but the logical conclusion of Elvis gradually asserting himself against the Colonel and his publishing cabal.

The thorough booklet by Peter Guralnick - the most musically illuminating essay ever written about Elvis - places the developments in context. When Elvis entered the small RCA studio in Nashville on March 20, 1960, after his two-year army stint, the pressure was on. He had to have a single out by the end of the week, and it had to be good. Twelve hours later, he had six cuts down without any strain. The results were consistently excellent, and ran from rock’n’roll (‘Stuck On You’) to doo-wop (‘Fame and Fortune’) to blues (‘It Feels So Right’).

Ten days later he was back in the studio. The single was out, so Elvis felt relaxed, exuberant. As he said the day he arrived at Sun Studios, he could sing all kinds of music. In this second session he covered pop, gospel, R&B; the first of the grandiose Italian ballads in which he could emulate his idol Dean Martin (‘It’s Now Or Never’), and the grittiest blues he ever recorded (‘Reconsider Baby’).  The album was intense, vibrant and creative; they called it Elvis Is Back.

The album was intense, vibrant and creative; they called it Elvis Is Back.

By the time he returned to Nashville to record the follow-up, aptly titled Something For Everybody, he’d made two films, GI Blues and Flaming Star. Both had soundtracks, and the GI Blues album far out-sold Elvis Is Back; Blue Hawaii was the biggest album of his career. The pattern was established, and the rot soon set in. Elvis’s next non-movie album was called Pot Luck, and it sounded like it. He wouldn’t make another studio album until 1967.

There was the odd single that showed he still had it, when he believed in the material: the assured Pomus-Shuman double banger, ‘Little Sister’ and ‘His Latest Flame’, ‘Return to Sender’, ‘Can’t Help Falling in Love’, ‘Devil in Disguise’, ‘Viva Las Vegas’. With Elvis Is Back it looked as though he was going to fulfil all the promise of the 50s. As Guralnick says, “The only thing that stood in his way was success.” Success won. With so little effort needed to make the movies (three a year) and the soundtracks that sold so well, why bother to take risks?

Elvis had no A&R person looking after his creative interests; RCA had shifted responsibility for him to the marketing department - and Colonel Parker was only interested in maximum returns for minimum outlay. Therein was the core of the problem. Parker would only let his boy record songs published by Hill & Range, who co-owned Elvis’s two publishing companies. A team of hack writers churned out songs for the movies. Parker argued that if his boy couldn’t have a cut of the publishing action, his boy wouldn’t cut the song. So good songwriters quickly stopped offering their songs.

(An example of the Colonel’s style: when Lionel Newman, the Hollywood conductor and Randy’s uncle, visited New Zealand in 1985, he told me a story about Love Me Tender, on which he worked. They needed one more song as a title track, so Newman recommended one written by his pianist. Parker loved it. “That’s a fine song we’ve just written, Elvis!” he said. ‘Love Me Tender’ is credited Matson/Presley.)

It was an impasse, says Guralnick. “Music had always been the motivating force of his life, it had been his one sure source of emotional expression and release, but with both live performance and serious recording efforts effectively cut off, he turned increasingly to other avenues of spiritual expression.”

It was an impasse, says Guralnick. “Music had always been the motivating force of his life, it had been his one sure source of emotional expression and release, but with both live performance and serious recording efforts effectively cut off, he turned increasingly to other avenues of spiritual expression.”

When the sales of the soundtracks began to plummet - ie, they didn’t reach the Top 10 - it was time for a change. In May, 1966, Elvis left the sterile Hollywood musicians behind and returned to Nashville to record a gospel album with a new producer, Felton Jarvis. The oceans of mediocrity were about to be turned back.

When Elvis died, that lonely night on the toilet in 1977, it was Felton Jarvis who said the immortal words, “It was as though someone told me there were gonna be no more cheeseburgers in the world.” At the time I thought that summed up the crass side of the Elvis myth. But I didn’t understand the full story, or the part Jarvis had played in it.

Jarvis had begun his career in the late 50s as an Elvis imitator; he recorded ‘Don’t Knock Elvis’, then had greater success producing a more gifted Elvis imitator Marvin Benefield (re-naming him Vince Everett after Elvis’s character in Jailhouse Rock). So he knew his stuff, and, unlike the unadventurous Chet Atkins, who’d been producing Elvis since his return, he was energetic and enthusiastic. How’d he get the job? “Chet didn’t like staying up late,” explained Jarvis.

Elvis was once asked if he knew many gospel songs. “I think I know all of them,” he replied. Gospel would always be the musical hearth to which he’d retreat in times of need. (There’s a telling scene in This Is Elvis, in which he starts talking dirty in the back of a limo. “The microphone’s on,” someone warns. Elvis gives a nervous laugh, then sings, “What a friend we have in Jesus …”)

Elvis was once asked if he knew many gospel songs. “I think I know all of them,” he replied. Gospel would always be the musical hearth to which he’d retreat in times of need. (There’s a telling scene in This Is Elvis, in which he starts talking dirty in the back of a limo. “The microphone’s on,” someone warns. Elvis gives a nervous laugh, then sings, “What a friend we have in Jesus …”)

Elvis – seen above with Mahalia Jackson – felt at home during the sessions for How Great Thou Art. He slipped easily from the sacred songs to secular diversions such as the raunchy ‘Down in the Alley’ and the exquisite Dylan obscurity ‘Tomorrow is a Long Time’ (this was 1966, remember). Young pianist David Briggs brought pure gospel chords to ‘Love Letters’ and hillbilly guitarist Jerry Reed provided a country edge to ‘Guitar Man’. They enjoyed recording the latter song so much they romped seamlessly into ‘What’d I Say’ (deleted on the single but included here). ‘Big Boss Man’ was just as exhilarating - but then the business interests intervened. Jerry Reed was hit up for the publishing rights to his song. He refused, and left; and so did the spirit of the session.

Those songs (many were used to pad the Spinout soundtrack) laid the groundwork for The Great Comeback of 1968-69: the TV special and the sensational soul album From Elvis in Memphis that are now legend. For the first time since the Sun sessions in 1955, Elvis returned to a Memphis studio. The city was just peaking as a recording centre. The players, producer, songs and artist all connected to make sublime music; a perfect mix of soul, country and gospel. Among the singles were ‘In the Ghetto’ and ‘Suspicious Minds’, and Elvis had to fight the Colonel to record them without owning the publishing. (Parker had also wanted the TV special to be all Christmas tunes.)

Once again, Elvis was back as a creative force. I’ve always had a vague memory of another TV appearance around the turn of the 60s, in which he says, “I’ve been away a while and some great songs have been written.” It’s gotta be the Beatles, I thought. And sure enough, he launched into ‘Hey Jude’, one of the many gems on this box-set (a studio version cut in Memphis but not released until 1972).

Once again, Elvis was back as a creative force. I’ve always had a vague memory of another TV appearance around the turn of the 60s, in which he says, “I’ve been away a while and some great songs have been written.” It’s gotta be the Beatles, I thought. And sure enough, he launched into ‘Hey Jude’, one of the many gems on this box-set (a studio version cut in Memphis but not released until 1972).

After the Memphis sessions, Elvis had a new energy, which the Colonel quickly dissipated through another cynical, soul-destroying money spinner: Las Vegas. Elvis’s career in the 60s was a roller-coaster of creative highs and lows. It’s easy to blame the Colonel - and, given the greed and exploitation, justifiable. But, as for Brian Epstein and the Beatles, there were no rules for handling the massive success, there was no precedent to guide artistic development. We can have “Given the material and the manager” arguments forever. What we’ve got are the recordings; given the odds, it’s remarkable how many of these 130 tracks are not just listenable, but full of wonder.

© Chris Bourke