31 December 2012

Olympian

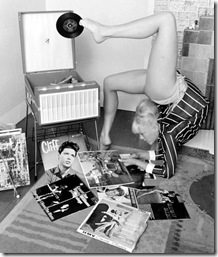

Aretha Franklin live in Amsterdam, 1968.

Monitor: Open Culture

06 December 2012

From St Kilda to King’s Cross

Paul Kelly’s “song memoir” How to Make Gravy (Penguin, 2010) is as expansive and rich in gems as Australia itself. This is no conventional autobiography, and all the better for it. Written using an A-Z of his songs as its structure, it is digressive, thoughtful and honest. He is a raconteur with a sense of history and a guitar at hand to illustrate a point.

He talks of the joys of big families, touring the outback choking on the tales of Slim Dusty, wasting years and wasting relationships while dabbling in heroin, songwriting friends such as Dragon’s Paul Hewson and Cold Chisel’s Don Walker (“the Clint Eastwood of Australian music”), collaborations with Aboriginal musicians, a pro-active commitment to social justice, and endless summers of cricket. As asides, lyrics and lists (great opening lines for songs, a recipe for gravy, Gary Puckett and the Union Gap’s concept album). The best songs keep nagging you, “like a tongue with a loose tooth”. So does this. Two years after reading it I still don’t feel I’ve quite scraped the best bits off the pan.

A long televised interview with Kelly, conducted by the Go-Betweens’ Robert Forster, is recommended. So too is Forster’s thoughtful essay on Kelly’s work, “Thoughts in the Middle of a Career”, written for The Monthly.

20 November 2012

Take it to la bridge

Reading the London Independent’s fascinating obituary of French pretty-boy singer Frank Alamo – the leading exponent of the 1960s yéyé genre – I came across a sentence about his rivals Johnny Hallyday and Claude François. All three recorded French-language adaptations of UK and US hits, occasionally covering the same songs, eg ‘Da Doo Ron Ron’ and ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’. This is how the obituary described Alamo’s competitors:

Hallyday, in the late 1950s, based his moody persona on Elvis Presley and the US rock’n’rollers, while François drew on James Brown and Motown and surrounded himself with dancing girls – les Clodettes, inspired by Ike and Tina Turner's Ikettes – but the clean-cut Alamo gave them a run for their money …

A French James Brown, go-go-ing Clodettes? I had to see this. The song I found is called ‘Belinda’.

Still, delving into old French pop singers required a nostalgic re-visit to Claude Nougaro’s ‘Anna’.

06 November 2012

When the day is dawning

‘Just a Little Lovin’ is the perfect opening track to the perfect album, Dusty in Memphis. Written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, it works like an overture to the 40-minute emotional opera that is Dusty Springfield’s 1969 classic.

But what a brilliant song, recently revived by Shelby Lynn for her Springfield tribute album, Just a Little Lovin’. Is there a better opening than, “Just a little lovin’, early in the morning / beats a cup of coffee, for starting off the day…”

This is all a preamble to a discovery recently made, of 60s bombshell Elke Sommer performing the song with a charming accent on The Dean Martin Show. Not so charming is the bibulous host, who undercuts any message the song has by donning his tuxedo and fleeing. Martin did have issues.

Martin himself recorded a song called ‘Just a Little Lovin’ but it wasn’t the same song. Written by Eddy Arnold, it had the sub-title “Will Go a Long Way”, and was also recorded by Ray Charles. After Springfield released the Mann/Weil classic, though, it was later recorded by Sarah Vaughan and Carmen McRae. Now there’s a vote of confidence in a song – and a performance.

02 November 2012

01 November 2012

Raiders of a Lost Art

Discussing Kael's response to Raiders of the Lost Ark, the George Lucas-Steven Spielberg 1981 tribute to the old movie serials, Kellow's summary encapsulates the disappointment so many feel when watching talented filmmakers waste their time on action-packed but emotionally empty epics. Raiders, writes Kellow,

... appealed to an incredibly wide base, but Pauline regarded it as a perfect symbol of the rise of the marketing executives; in her review of the picture, she pointed out that marketing budgets often surpass total production budgets, a practice that "could become commonplace." She found Raiders didn't allow you "time to breathe - or to enjoy yourself much, either. It's an encyclopedia of high spots from the old serials, run through at top speed and edited like a great trailer - for flash." At last, she could see the direction in which Jaws had led. Its excesses were especially a pity, she thought, because both Lucas and Spielberg were loaded with movie-making talent. She observed that if Lucas "[wasn't] hooked on the crap of his childhood - if he brought his resources to bear on some projects with human beings in them - there's no imagining the result." But it's doubtful that Lucas paid attention to her admonishment - not in the face of the $230 million gross racked up by Raiders.

Brian Kellow, Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark (Viking, 2012), p295.In response to Disney's purchase this week of the Lucas/Star Wars empire, Richard Brody, the New Yorker's film blogger (is he too geekish to be an actual columnist?), has just written a positive post about US independent filmmaking.

26 October 2012

Retreat may be masterly

Even to the late 1960s, when TV news footage of important events such as the moon landing had to travel in film canisters to New Zealand, the newsweeklies could be up to date with a week’s events. For all their regurgitated prose, there was some great writing: Newsweek journalists were awarded bylines first, while at Time, Jay Cocks on film and music, and Robert Hughes on art, were stylists at the height of their game. Newsweek may have had a circulation of 3,130,600 in 2006, falling to 1,524,989 by 2011, but it has been on the ropes for years. Sometime in the 1980s, the Australian and New Zealand edition was subsumed into The Bulletin, itself now dead for five years.

05 October 2012

Town v Country

He is playing his persona to the hilt – getting kicked out by bookshops, giving his dogs away, landlady issues – but gives Kevin Ireland credit for turning him into a writer: “Twenty-five times he made me write my first story and then he published it. That was the start.”

And there is a reference to a comment about his success that was apparently quoted often: “The dough’s got into me blood.”

03 October 2012

Fish wrapping

Salient – Victoria University’s student magazine – is these days stapled, A4 and 48 pages. It is smartly edited (Asher Emanuel & Ollie Neas) and also elegantly designed (Racheal Reeves), albeit imitative of The Believer. But whereas much of The Believer is unreadable due to its slippery, affected prose, with Salient it’s simply the typography. Grey type on bleached white paper, black type on dark grey paper, and all in 4 point. Don’t they want their writers to be read? A pity, as the content is strong, like much of the student media (see Peter McLennan’s summary of a Craccum campaign about an Auckland University scandal here) – though we are yet to see the effect of the vindictive voluntary student unionism bill. Two items from the October 1st “Power” issue:

2. ‘The Measure of a Manhire’

Rob Kelly interviews Bill Manhire the mild-mannered Superpoet on his departure from VUW. Manhire describes the 1960s at Otago, when – thanks to the university’s Burns fellowship – a few New Zealand writing role models finally entered his sphere (they weren’t part of the English curriculum at the time): Baxter (“behaving badly”), Janet Frame (“scuttling along corridors”), Maurice Gee, Hone Tuwhare. These writers “became very influential, but more as examples of people who had committed their lives to doing the thing that mattered. So it was great to go to the Captain Cook and drink beer with Hone, but also you knew that … I mean, he would arrive with poems and sort of hand them out, and all the local alcoholics would give him advice and he’d go away with a much worse poem than he arrived with. A sort of anti creative writing workshop.”

3. ‘I Moustache You Some Questions’

Chris McIntyre interviews TVNZ’s Mark Sainsbury, just prior to the news that Close Up is closing shop. Is it hard defending his throne against the likes of Hosking and Henry? “It’s one of the top jobs, so people want that job, but they can’t have it … Paul Henry made no secret he wanted that job, he’s now working on breakfast in Australia. I mean, draw what you like out of that.”

4. Must Try Harder

He actually comiserates rather than scores points as he finds Lenny Kaye dissing Exile on Main Street, Jon Landau underwhelmed by Sticky Fingers, Langdon Winner finding After the Gold Rush rushed (“I can’t listen to it at all”). And Ed Ward, who was often excellent (on the Band, Texan country rock and 1950s rock’n’roll) on Abbey Road:

Side two is a disaster ... The slump begins with ‘Because’, which is a rather nothing song ... the biggest bomb on the album is ‘Sun King’,which overflows with sixth and ninth chords and finally degenerates into a Muzak-sounding thing with Italian lyrics. It is probably the worst thing the Beatles have done since they changed drummers. This leads into the “Suite” which finishes up the side. There are six little songs, each slightly under two minutes long, all of which are so heavily overproduced that they are hard to listen to ...

Ward wasn’t alone of course, in the New York Times Nik Cohn agreed, though not about the “Suite” (“For 15 minutes, tremendous”), and two years earlier Richard Goldstein dissed Sgt Pepper, following it up in the Village Voice with a similarly well-argued piece about the reaction called “I Blew My Cool Through the New York Times.”

Rolling Stone’s response? The managing editor Evie Nagy sniffed: “I say this genuinely without bias, that person's time could have been so much better spent. At least make it funny.”

5. Gambling with Gout

Speaking of the Fabs, I remain to be convinced by Magical Mystery Tour, though the connections with Python are plausible. But just released, by the BBC’s Arena programme, are five minutes of outtakes in which the Beatles buy fish’n’chips while on their bus journey (think Ken Kesey meets Beano).

There'll be time enough for countin’ when the dealin’ is done.

25 September 2012

Tour de Farce

1. Dot Comedy of Errors

The D*tc*m saga seems destined to channel surf through the popular culture possibilities, from the Keystone Cops to SWAT. Now, it’s Austin Powers. Scriptwriters would turn away in horror from such a polyglot set up, in which a government (led by Mr Magoo) chases

2. Citizen Pope

In just 74 years, Jeremy Pope achieved an enormous amount: for New Zealand, and internationally. A lawyer, he spent much of his life campaigning for human rights and the environment, and against corruption. At Te Ara’s Signposts blog, Jock Phillips has posted a tribute that details much of it: his work on the Save Manapouri campaign, as a legal adviser to the 1975 Maori land march, and editing – with his wife Diana – the hugely successful Mobil travel guides to the North and South Islands, which ran to several updated editions. Pope left New Zealand in about 1981, one of many refugees from the reign of Muldoon (he had been involved with the “Citizens for Rowling” lobby). New Zealand’s temporary loss was the world’s gain: Pope co-founded the anti-corruption organisation Transparency International. A 2009 interview with him can be heard at Radio New Zealand below.

3. Hang on a Minute

4. Publish and Be Damned

21 September 2012

The Maori-Memphis connection

Update: now I’ve got my copy back again, the sparse credits say that the album was produced by N Rosenberg, and engineered by Steve Stepanian. It doesn’t say where it was recorded but in November 1970 the album was re-mixed at Universal Recording Studios, Memphis TN. Its catalogue number was MS1001, and Memphis Records was part of the Memphis Corporation, at 261 Chelsea Building, Memphis – probably an office up a few flights of stairs.

19 September 2012

Please Mr President

"No other Western industrialized nation would’ve elected a black president. I’m proud of this country for having elected Obama in 2008. But from the beginning of his term, I noticed a particular heat to conversations that wouldn’t ordinarily generate that kind of passion: The budget, appointments, health care.” He continues, “I think there are a lot of people who find it jarring to have a black man in the White House and they want him out. They just can’t believe that there’s not a more qualified white man. You won’t get anyone, and I do mean anyone, to admit it.

“I often write songs in character. You can’t always trust or believe the narrators in my songs. So why listen? Good question.

“Anyway the guy in this song may exist somewhere. Let’s hope not. Vote in November.”'I'm Dreaming' is available as a free download at the site of his record label Nonesuch.

04 September 2012

Sleepin’ on the Job

1. Royalty

1. RoyaltySinatra lyricist Sammy Cahn was often asked, Which came first – the words or the lyrics? His answer: “The phone call”. As a listener, for me it’s always the melody, but Paul Hester once pointed out how that’s not so for everyone (particularly women). “There’s a reason lyricists get half the royalties.” With the passing of Hal David late last week, we farewell a certain style of lyricist whose smarts never elbowed out accessibility. The team of Bacharach and David was an anomaly in the so-called Swinging Sixties: Burt Bacharach may have looked ready for the Playboy mansion, while David dressed for the golf club. But on over 700 songs David’s skill with a lyric harked back to Johnny Mercer, yet touched millions unmoved by psychedelics but by pure human emotions. A testimony to David’s breadth is the number of different songs that obit headline writers have used. Every song has a surprise that makes them unforgettable: an everyday image, an unexpected metre or rhyme. ‘I Say a Little Prayer’ sees the female singer rushing to her day job, putting on her makeup, running for the bus; ‘I’ll Never Fall in Love Again’ rhymes pneumonia with phone yer. In ‘Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head’, a casual guy’s feet are too big for his bed; nothing seems to fit. Davis makes a clever segue from “cryin’s not for me” to the internal rhymes of “nothing’s gonna stop the rain by complainin’”, and “the blues he sends to meet me won’t defeat me”. In the middle eight of ‘Do You Know the Way to San Jose’ David seems to take the baton from Roger Miller’s ‘King of the Road’ – “LA is a great big freeway / put a hundred down and buy a car” – and pass it to Guy Clark: “If I get off of this LA freeway / without getting killed or caught.” But ‘Jose’ also shows how teamwork was essential to their craft: where the emphasis falls in “and parking cars and pumping gas” is crucial to making simple imagery profound.

2. Prodigal

Jesus Christ was found last week in Taranaki, after more than 10 years in the wilderness. Jim Allen’s mahogany sculpture of Christ was the centrepiece of John Scott’s 1961 design of the Futuna Chapel in Wellington, which is regarded as one of New Zealand’s architectural masterpieces. A mention on RNZ’s Saturday Morning programme by architect David Mitchell led one listener to recall seeing it in someone’s lounge. This week the Wellington detective who discreetly explored the lead drove up to Taranaki to bring the statue back. In a perfect world, a film crew would follow him on the journey, Christ sitting up in the back of a convertible; the soundtrack playing is from Jim White’s doco Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus.

Jesus Christ was found last week in Taranaki, after more than 10 years in the wilderness. Jim Allen’s mahogany sculpture of Christ was the centrepiece of John Scott’s 1961 design of the Futuna Chapel in Wellington, which is regarded as one of New Zealand’s architectural masterpieces. A mention on RNZ’s Saturday Morning programme by architect David Mitchell led one listener to recall seeing it in someone’s lounge. This week the Wellington detective who discreetly explored the lead drove up to Taranaki to bring the statue back. In a perfect world, a film crew would follow him on the journey, Christ sitting up in the back of a convertible; the soundtrack playing is from Jim White’s doco Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus. 3. Show time

The much-missed Word magazine offered a weekly podcast in which the editors told anecdotes, reflected on music and modern life, and interviewed the occasional guest. It was a great way of connecting with their readers, far more genuine than some gimmick thought up by a marketing department. The Word didn’t have one of those, nor did it have enough paying advertisers. A podcast earlier this year was a gem: their guests were the authors Paul Charles and Stanley Booth. Charles has worked in the UK music business and written a series of mystery novels, but his new bookThe Last Dance (New Island) is different. It’s a novelised history of the 1960s’ Irish showband phenomenon, told as a fictional biography of an invented band, the Playboys of Castlemartin. These showbands are often spoken of with derision by the rock star children whose parents may have met at their dances: I have heard Bono and Bob Geldof almost bust blood vessels describing their naffness and their place in an earlier, oppressed Ireland. We invented hipness is the message, ignoring that without the Irish showbands, there would be no Van Morrison, who served his time in the Monarchs (where he learnt his chops arranging brass). What was intriguing about the podcast was the way Charles’s description suggested connections between the Irish and Maori showbands. Both were prominent simultaneously in the early 1960s, and both shared an eclectic approach to music that emphasised humour, dancing and musicianship over originality. The Last Dance is flawed: for a novel it desperately needs a fact checker, Charles too often places the important clause of a sentence right at the very end, and the plot often veers into soap opera. But in its own naive way it captures a lost world, and is great craic. Pictured are the Vikings from Dundalk.

The much-missed Word magazine offered a weekly podcast in which the editors told anecdotes, reflected on music and modern life, and interviewed the occasional guest. It was a great way of connecting with their readers, far more genuine than some gimmick thought up by a marketing department. The Word didn’t have one of those, nor did it have enough paying advertisers. A podcast earlier this year was a gem: their guests were the authors Paul Charles and Stanley Booth. Charles has worked in the UK music business and written a series of mystery novels, but his new bookThe Last Dance (New Island) is different. It’s a novelised history of the 1960s’ Irish showband phenomenon, told as a fictional biography of an invented band, the Playboys of Castlemartin. These showbands are often spoken of with derision by the rock star children whose parents may have met at their dances: I have heard Bono and Bob Geldof almost bust blood vessels describing their naffness and their place in an earlier, oppressed Ireland. We invented hipness is the message, ignoring that without the Irish showbands, there would be no Van Morrison, who served his time in the Monarchs (where he learnt his chops arranging brass). What was intriguing about the podcast was the way Charles’s description suggested connections between the Irish and Maori showbands. Both were prominent simultaneously in the early 1960s, and both shared an eclectic approach to music that emphasised humour, dancing and musicianship over originality. The Last Dance is flawed: for a novel it desperately needs a fact checker, Charles too often places the important clause of a sentence right at the very end, and the plot often veers into soap opera. But in its own naive way it captures a lost world, and is great craic. Pictured are the Vikings from Dundalk. 4. Pop sociology

Pat Long’s History of the NME (Portico) sketches out the roller-coaster tale of what was once the world’s most influential pop paper. Long is no stylist, but his book is more interesting that the solipsistic recent memoir of the paper’s 1970s junkie star, Nick Kent (Apathy for the Devil). From its

beginnings championing Vera Lynn through to the troubled post-Britpop digital era, the NME has had many periods of boom, and never quite succumbed to bust. But Long, a recent staff writer, captures well the era in which the paper lost its way: the early 1980s, when NME writers Ian Penman and Paul Morley made up for their ignorance about music, history, earlier rock journalism and satisfying readers by

beginnings championing Vera Lynn through to the troubled post-Britpop digital era, the NME has had many periods of boom, and never quite succumbed to bust. But Long, a recent staff writer, captures well the era in which the paper lost its way: the early 1980s, when NME writers Ian Penman and Paul Morley made up for their ignorance about music, history, earlier rock journalism and satisfying readers by“… attempting to write in a way that was alternately brave and baffling, employing punctuation like a weapon, conjuring images that were abstract and evocative and occasionally downright meaningless. It was gloriously provocative but at times very long-winded and egocentric writing, inspired by French philosophers Michel Foucault, Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida and the work of the Frankfurt School of dissident Marxist social theoreticians. Whether this approach had any place in a weekly music paper is a moot point, but suddenly the pages of NME assumed something of the atmosphere of the staff common room of the philosophy department of a small provincial university.”5. Warped

Part of the NME’s success - especially in the mid to late 1970s - was that it covered more than music. This undoubtedly influenced The Word, whose editor Mark Ellen and co-founder David Hepworth both worked the NME under the editorships of Nick Logan and Neil Spencer. Perhaps the only positive to come from the demise of The Word is that David Hepworth is finding more time to update his reflective blog, which covers not just music but sport, literature, history, media, publishing and parenting (from the perspective of someone who came of age in the era of Harold Wilson). Here are his Ten Laws of Record Collecting.

17 August 2012

08 August 2012

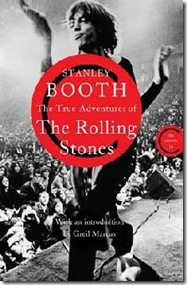

Down the Road Apiece

Stanley Booth was the Zelig of rock’n’roll writing. A Southern hipster determined to become a serious writer, he was present in the Memphis studio when Otis Redding wrote ‘Dock of the Bay’, and he witnessed the Rolling Stones record ‘Brown Sugar’ in Alabama. He penned the liner notes to Dusty in Memphis, was a confidante of revered record producers Jerry Wexler and Jim Dickinson, and a friend and patron of street-sweeping Memphis bluesman Furry Lewis. That Booth came from the same small town in Georgia as Gram Parsons just confirms his knack of being in the right place at the right time.

It must have seemed that way when, after writing prescient, lyrical pieces on BB King and Elvis Presley for Esquire and Playboy in the 1960s, he was commissioned to write a book about going on the road with the Rolling Stones on their 1969 US tour.

The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones took Booth 15 years and almost cost him his life. The book became a critics’ favourite but was a box-office disappointment. It didn’t enable him to get on with his real ambition – to become a streetwise successor to William Faulkner – but aficionados of music writing consider it to be the one book in an over-published, undisciplined genre that approaches literature.

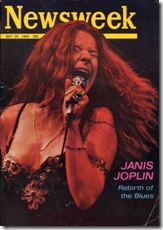

Booth was originally disdainful of white musicians trying to perform R&B; in a 1968 article he was scathing of a chaotic Janis Joplin performing alongside dignified Memphis soul legends. But he became fascinated by the Stones

The Stones’ 1969 tour is notorious for climaxing with Altamont, a free concert that became an apocalyptic nightmare. The tour also produced the live album Get Yer Ya Ya’s Out and the classic cinema verite documentary Gimme Shelter. The winter of 1969was one of discontent, of bad dope and bad vibes, with Nixon in th e White House, troops stuck in Vietnam, students protesting and generations clashing.

Booth’s book weaves through several stories simultaneously. There is the tour itself, with the writer having an access-all-areas pass and a rapport with Keith Richards that has professional benefits and lifestyle drawbacks. Almost subliminally, the Stones’ history is compellingly related using anecdotes from the participants. Booth describes the unlovable Brian Jones, his decline and inevitable demise. And he also tells his own story: a swift ascent to become a writer who then tumbles, like Icarus, from flying too close to the sun. The Altamont festival provides a chilling climax to the strands of his narrative. On stage beside the band, he stands transfixed but impotent as several Hell’s Angels viciously beat members of the crowd with pool cues.

The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones is written like a non-fiction novel. In Cold Blood was an influence, though Truman Capote’s own attempt at writing about the band’s 1972 tour stalled from writer’s block and a cultural disconnect. Booth was immediately on the Stones’ wavelength. His Southern accent, upbringing and contacts provided an entree: he could act as their regional interpreter. By appropriating R&B, rock’n’roll and country music, and adding their own Dartford Delta seasoning, the Rolling Stones produced their finest albums Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street, inventing a trans-Atlantic music steeped in popular culture and hedonism.

With an introduction by Greil Marcus and an afterword by the author, this handsome reissue by Canongate coincides with the Rolling Stones’ 50th anniversary. But it conveys their story far more evocatively than any sanctioned coffee-table book. To Booth’s annoyance, the 1984 US edition was melodramatically renamed Dance With the Devil. His own title – The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones – hints of James Fennimore Cooper. Booth had aspirations towards Raymond Chandler, and affectations to William Faulkner. But the one thing his original publisher did right was see the link to Edgar Allen Poe.

First published at Beattie’s Book Blog

03 August 2012

Waiting On a Friend

1. Making Baby Float

With minutes to spare, the IIML twitter alerts me to a concert taking place nearby at the grandly named New Zealand School of Music. The Spaces In Between is another collaboration between pianist and composer Norman Meehan, poet Bill Manhire and singer Hannah Griffin. It’s been a couple of years since I saw them at St Andrews on the Terrace, and in that time the careful treatments have gelled into compelling art songs, and Griffin’s performance has an added depth and assuredness. The poems given musical settings include David Mitchell’s witty ‘Aesthetics’ (I last saw Wellington’s leading Beat down the road nearby in John Street), Baxter’s ‘High Country Weather’ (appropriately spare), Manhire’s ‘Buddhist Rain’ and – with a gospel vocal trio - David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’. Meehan introduced Hone Tuwhare’s ‘To Elespie, Ian & their Holy Whanau’ as “curiously named”, which would be news to the peace-loving Prior family. But he has a lovely touch on the Steinway, his arrangements having a gentle humour, and at one point guest Colin Hemmingsen’s clarinet provides an oxymoron: a joyful lament. Keith Hill’s recent documentary on this troupe is called Persuading the Baby to Float.

2. Laus Tibi Domine

Art, Keith Richards once said, is just short for Arthur. Turning poetry into songs is a risky endeavour, the results are often so arch. Denis Glover apparently grumbled at Douglas Lilburn’s 1954 settings of his ‘Sings Harry’ poems, and it has to be said something more earthy would have been more suitable. Meehan’s success reminded me of Dave Dobbyn’s deeply moving treatment of James K Baxter’s ‘Song of the Years’, which opens, “When from my mother’s womb I came / Disputandum was my name …” It was a match made in heaven, so perhaps Dobbyn should look to updating ‘Sings Harry’: like Baxter, Glover is a kindred spirit. Charlotte Yates, who commissioned Dobbyn’s song for the Baxter album, wrote that his use of repetition “turned the somewhat lad-least-likely last line of the poem ‘Laus tibi, Domine!’ into an utterly joyful and triumphant outro.”

Art, Keith Richards once said, is just short for Arthur. Turning poetry into songs is a risky endeavour, the results are often so arch. Denis Glover apparently grumbled at Douglas Lilburn’s 1954 settings of his ‘Sings Harry’ poems, and it has to be said something more earthy would have been more suitable. Meehan’s success reminded me of Dave Dobbyn’s deeply moving treatment of James K Baxter’s ‘Song of the Years’, which opens, “When from my mother’s womb I came / Disputandum was my name …” It was a match made in heaven, so perhaps Dobbyn should look to updating ‘Sings Harry’: like Baxter, Glover is a kindred spirit. Charlotte Yates, who commissioned Dobbyn’s song for the Baxter album, wrote that his use of repetition “turned the somewhat lad-least-likely last line of the poem ‘Laus tibi, Domine!’ into an utterly joyful and triumphant outro.”

3. True Adventures

After a gap of 27 years, I’ve been re-reading the one book about rock music that approaches literature: Stanley Booth’s classic The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, about the 1969 US tour and so much more. First published in 1984, and recently reissued by Canongate, and I’m looking forward to reviewing it soon. It’s meant a revisit to the canon, especially Let it Bleed and Sticky Fingers (Exile got a workover at the time of its reissue in 2010). One of the standout moments is his observation, “There were no grownups among us.” I wish I could find the actual line again, but at a time when books fight to justify their space, this one has returned like a prodigal son.

4. Someone to protect

Which makes me think of a new earworm for the day, written circa 1973, released in 1981. Sax solo by Sonny Rollins.

5. Diversions

The IIML twitter also provides “A website that some folk might find handy.”

08 June 2012

50 Ways to Leave an Industry

50 Most Important People in New Zealand Music (2003)

50. James Reid – the Feelers

49. 8 Foot Sativa

48. King Kapisi

47. Brent Eccles – promoter

46. Murray Cammick – Wildside, Rip It Up co-founder

45. Teina Herzer and Aaron Dustin – founders, nzmusic.com

44. Terence O’Neill Joyce – RIANZ

43. Mike Chunn – APRA

42. Tyson Kennedy – Steriogram

41. Campbell Smith – artist manager

40. Bridgit Darby

39. Adrien De Croy – York St Studios owner

38. Chris Hocquard – lawyer, Amplifier founder, Bfm chair

37. P. Money

36. Bernie Griffin – chair IMNZ, owner Global Routes

35. Cath Anderson – NZ Music Commission

34. Sean Coleman and Shaun Joyce – Sounds

33. Terry Anderson – music buyer, The Warehouse

32. Daniel Wrightson – Juice TV

31. John Pilley – National Radio music manager

30. David Rose – MD, Satellite Media Group

29. Damian Alexander – Blindspott

28. Bic Runga

27. Pete Rainey and Glenn Common – Rockquest

26. Nesian Mystik

25. Helen Clark

24. YDNZ and Brother D – Dawn Raid

23. Kog Transmissions

22. Ian Fraser – TVNZ

21. Michael Bradshaw – BMG

20. James Southgate – Warners

19. Chris Caddick – EMI

18. Mark Ashbridge – FMR

17. Michael Glading – Sony, RIANZ chair

16. Adam Holt – Universal

15. BNET

14. David Brice – PD, ZM Network, Classic Hits

13. Leon Wratt – PD, The Edge

12. Brad King – PD, The Rock

11. Andrew Szusterman – PD, Channel Z

10. Rodger Clamp – programmer, More FM etc

9. Judith Tizard – politician

8 and 7. Dion and Jimmy – the D4

6. Dolf De Datsun – the Datsuns

5. Brent Impey, CanWest

4. Drinks: Coke, Pepsi, Red Bull, DB Export etc

3. Che Fu

2. Brendan Smythe – NZ On Air

1. Neil & Tim Finn

“Must Mentions” – Arthur Baysting – NZ Music Commission; Dave Dobbyn; DJ Presha – Subtronix label; Mai FM; Jasper Edwards, Fabric Club, London; DJ Sir Vere; Stephen McCarthy – bands.co.nz; Venue Owners: King’s Arms, the Temple, Bar Bodega.

26 April 2012

The Limited Express

25 April 2012

Highway 61 Blues

course, and also Tumbleweed Connection). Twenty years ago I visited Coahoma County, Mississippi, where so many blues and R&B artists were born. I crossed the bridge to West Helena, Arkansas, and found myself in Levon territory, where Sonny Boy Williamson broadcast King Biscuit Time, and Helm had seen travelling minstrel shows. Just up the road was his birthplace, Marvell, and the place where his father farmed, Turkey Scratch. A few months later I got to talk to Tony Joe White about this; he rued the fact that gaudy casinos had changed much of this area irrevocably.

course, and also Tumbleweed Connection). Twenty years ago I visited Coahoma County, Mississippi, where so many blues and R&B artists were born. I crossed the bridge to West Helena, Arkansas, and found myself in Levon territory, where Sonny Boy Williamson broadcast King Biscuit Time, and Helm had seen travelling minstrel shows. Just up the road was his birthplace, Marvell, and the place where his father farmed, Turkey Scratch. A few months later I got to talk to Tony Joe White about this; he rued the fact that gaudy casinos had changed much of this area irrevocably. From Rip It Up, November 1993.

AS YOU DRIVE south out of Memphis down Highway 61, the trees and houses stop at the edge of the city limits. On either side of the narrow two-lane road, the horizon is almost bare, as far as the eye can see. This is the Delta, the land where the blues began.

Somehow this vast expanse of nothingness didn’t just produce cotton but an extraordinary number of blues singers, guitar players and songwriters. It feels timeless, and cut off from civilisation. But the music from this dirt table-top has had an effect all around the world.

Soon the small town of Tunica flashes by, a few gas pumps and motel signs. It was immortalised last year in ‘Tunica Motel’ by the great Southern songwriter Tony Joe White on his comeback album Closer to the Truth. “That was my fishin’ place, man,” he says, on the phone from Arkansas, west of the Mississippi. His deep drawl is so slow you could drive a tractor through his pauses.

“I went there and fished all the time with Duck Dunn, Booker T and the MGs’ bassplayer. It was a real laidback little place and still looks the same as it did years ago. But now, they’ve moved a gamblin’ riverboat into Tunica. There’s thousands of people coming into Tunica, gamblin’. It’s like the whole town is explodin’, so mah fishin’ hole is gone.”

“I went there and fished all the time with Duck Dunn, Booker T and the MGs’ bassplayer. It was a real laidback little place and still looks the same as it did years ago. But now, they’ve moved a gamblin’ riverboat into Tunica. There’s thousands of people coming into Tunica, gamblin’. It’s like the whole town is explodin’, so mah fishin’ hole is gone.”As the recent [1993] floods showed, the Mississippi is wont to break its banks occasionally. For centuries, before the levees were built and land cleared of its forests, swamps and bayous, the floods happened every year. And that made the topsoil of the Delta luxuriant, just right for cotton growing.

Writes Alan Lomax in The Land Where the Blues Began (Methuen, 1993):

“This treasure made its white owners not only rich but arrogant, although their main achievement had been to enslave and exploit the black labourers who actually cleared and tilled the land. The blacks had not only applied their inherited African agricultural skills to the development of the Delta, but had transformed remembered West African music into a new style, called the blues.”In 1942 Alan Lomax, a white folklorist, made a remarkable trip to the Delta that he’s just recalled in his equally remarkable memoir (all but unmentioned is John Work III, the black researcher who accompanied him). Ten years earlier, with his father, Lomax had discovered Leadbelly in a Louisiana prison. On this trip, recording blues singers on crude acetates for the Library of Congress, he met Robert Johnson’s mentor Son House and many others. Lomax’s memoir is not just an eloquent music history but a sensational tale of heartbreaking hardship, rollicking good humour and outrageous racism.

“You say we’ve got some talented niggers here in Tunica?” the sheriff asked Lomax in 1942.

“You’ve got the finest blues combination I’ve heard.”

“That so. Well, we’ll have to get um on the radio down in Clarksdale. What’re their names?”

“Well, Mister Son House is the...” I knew I’d made a mistake before the words were out of my mouth. The sheriff’s red face turned a beet colour.

“You called a nigger mister?!” he snapped. (Lomax)“I was raised on a cotton farm in Goodwill, Loosiana,” drawls Tony Joe White. “Goodwill was nothin’ but a church, a cotton gin and a pool hall. So every Saturday night everyone would go into Oak Grove, which is a little bigger. It had maybe 10 stores and a gas station and a Dairy Queen. So it was like going to a big town for us. We’d just go in and circle the Dairy Queen and wave at the girls and have a few cokes. It was laid back times.

“Most of the time we played at people’s houses. It was no band, it was just me and a rhythm guitar player. I used my foot on a coke box for something to drum. And people used to dance to it. At the time we was doin’ a lot of Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker, Elvis Presley. This was before I started writing.”

In 1969, White had his biggest hit with ‘Polk Salad Annie’. He mixed country, blues, rock’n’roll and fishing to create swamp rock. His songs are shaggy dog stories about backwoods preachers, granny-eating gators, nasty sheriffs and their “volupchuss” underage daughters. On his new album Path of a Decent Groove, he tells the story of ‘Mojo Dollar’. “It’s about a guy we used to call Wild Man Swamps. And that guy, he went crazy and went down to live in the swamps of Loosiana.

“That song came pretty quick. Some of ‘em take a long time. I don’t just sit down and try to write. I have to wait until my guitar comes to me, or a word or a line. It’s like, I haven’t wrote a song for eight months. A lot of people just get up every day and say, today I’m gonna write for three hours...for me, that seems like impossible.

“Most of the time it’ll start with a guitar thing in mah mind. I’ll be fishin’ or playin’ golf and a little guitar will keep goin’ through my head. I’ll sit down with it and say, hey, I’m here. Show me what you’ve got. And once they get started I’ll put in hard hours with ‘em. I’ll build a little campfire outside my house, get me an acoustic guitar and sit out there with a few beers at night and work with it. But until that happens, I don’t mess with it.”

It’s as though there’s something in the water that produces so many songwriters in the area. Great regional radio helped too, the black-run WDIA out of Memphis with DJs like BB King and Rufus Thomas, and out of Nashville, the legendary R&B show of John R. “That’s all I ever listened to,” says White, “except Elvis.”

Here’s Muddy Waters, in Creem, 1977:

“All the great bluesmen lived near each other. No one was more than 25 miles apart all along the Delta. Robert Johnson wasn’t more than just 10 miles from me to the east and I still never met him – just seen him at a distance. I listened to them all down the road – Skip James, Charlie Patton, Bukka White, Kokomo Arnold. But Son House was my number one man, when he played slide he was the greatest.”Last year [1992] I had a spare day in Memphis, so I drove south in a rental car with Tennessee plates. Nothing but bland country stations and classic rock on the dial, but plenty of meaningful road signs on the way. About two hours south on 61 is Clarksdale, a quiet town of rundown brick buildings about the size of Levin. It seems about as exciting, but the small museum testifies to the town’s musical significance. Among those born in the area are Muddy Waters, Sam Cooke, Aretha’s father, John Lee Hooker, Ike Turner, Junior Parker, Bo Diddley...

I took an unmarked road west and found myself accidentally on purpose on Stovall’s Road, which runs through Stovall’s plantation. I saw a tiny log cabin flash by, stopped, turned around, and there it was. Sitting without fanfare beside a back country road was the little shack in which Muddy Waters lived with his grandmother in the ‘30s. Here, in 1942, Waters took a break from ploughing cottonfields to play for Alan Lomax; this picture of Waters with Son Sims dates from around that time. Those Lomax recordings (recently reissued) lead to Waters’s career in Chicago. Follow the genealogical line through the Rolling Stones and it leads to Guns N’ Roses, and all that other big hair overblown blues on MTV.

I took an unmarked road west and found myself accidentally on purpose on Stovall’s Road, which runs through Stovall’s plantation. I saw a tiny log cabin flash by, stopped, turned around, and there it was. Sitting without fanfare beside a back country road was the little shack in which Muddy Waters lived with his grandmother in the ‘30s. Here, in 1942, Waters took a break from ploughing cottonfields to play for Alan Lomax; this picture of Waters with Son Sims dates from around that time. Those Lomax recordings (recently reissued) lead to Waters’s career in Chicago. Follow the genealogical line through the Rolling Stones and it leads to Guns N’ Roses, and all that other big hair overblown blues on MTV.Another conversation Lomax had in 1942:

“Little Robert [Johnson] learnt to play quicker than anybody we ever saw round this section,” said Son House. “He learnt from me and I learnt from an old fellow they call Lemon down in Clarksdale, and he was called Lemon because he had learnt all Blind Lemon’s pieces off the phonograph.”

I felt like shouting. Son House had laid out one of the mainlines in the royal lineage of America’s great guitar players – Blind Lemon Jefferson of Dallas to his double in Clarksdale to Son House to Robert Johnson.

“But isn’t there anybody alive who plays this style?” I asked.

“An old boy called Muddy Waters round Clarksdale, he learnt from me and Little Robert, and they say he getting to be a pretty fair player.”

The little shack was like a large, broken-down shoebox. In the 1990s it seemed so isolated it could have been in the Gobi desert. So imagine how exotic-Memphis, let alone Chicago, felt to Muddy Waters in the ‘30s. A few years ago, ZZ Top turned one of the shack’s wooden boards into a guitar to raise money for the Clarksdale blues museum. Now, a little sign asked that visitors didn’t take any toothpick sized bits as souvenirs. You sensed an international contingent of reverential fans had already made the pilgrimage: camera-happy Japanese, pedantic German scholars, list-making Brits, awe-struck New Zealanders. And all because they were moved by the same 12-bar magic.

The little shack was like a large, broken-down shoebox. In the 1990s it seemed so isolated it could have been in the Gobi desert. So imagine how exotic-Memphis, let alone Chicago, felt to Muddy Waters in the ‘30s. A few years ago, ZZ Top turned one of the shack’s wooden boards into a guitar to raise money for the Clarksdale blues museum. Now, a little sign asked that visitors didn’t take any toothpick sized bits as souvenirs. You sensed an international contingent of reverential fans had already made the pilgrimage: camera-happy Japanese, pedantic German scholars, list-making Brits, awe-struck New Zealanders. And all because they were moved by the same 12-bar magic.Robert Plant, from Q in 1990:

“On tour in Memphis, I rented a car and drove down to Mississippi, to Friars Point, as in the song. Very strange place, very African, very other-worldly. Sleepy, woodsmoke fires, big trees all around, burnt-out motels, deserted gas stations...”I headed down another narrow lane towards the levee. At a T-intersection was an old general store, its windows boarded up. Some black children played on the road outside three or four wooden houses. Above them loomed a water toward that said Friars Point. This was the place Robert Johnson sang about in ‘Travelling Riverside Blues’? “Just come on back to Friars Point, mama, and barrelhouse all night long.”

I couldn’t stop the engine, let alone get out of the car; the vehicle wasn’t just a goldfish bowl with central locking, but a way out. Not everyone was so lucky.

“Yessuh, I’s Mary Johnson. And Robert, he my baby son. But Little Robert, he’s dead.”Alan Lomax was just four years too late. Robert Plant and so many others, over 50. I headed across the Mississippi to West Helena, Arkansas, the home of Sonny Boy Williamson. In the little record store, the only albums that weren’t blues were by local hero Levon Helm of the Band.

“I love ole Levon’s music, man,” says Tony Joe. “But you know, I haven’t heard nothin’ from him in a long time. Since ole Clinton got to be president it’s like, Arkansas now, people talk about it all the time. I hope too many tourists don’t start coming up here. It’s a pretty quiet little place but I’m seein’ more and more campers nowadays. I’m so far back you almost need a four-wheel drive to get to my house. This ole farmhouse up in the Ozark mountains is about four hours from Memphis. There’s no television or anything, I’ve got a wood heater and a good fire going and I’ve got a front porch and a river – and that’s all you need.”

From such a backwater Tony Joe White and so many others have touched people of all cultures around the world. “My first hit was in Paris, France, before ‘Polk Salad Annie’,” he says. “It’d seem odd to me. I’d be sittin’ up there on stage, talkin’ just like I’m talkin’ to you. ‘Some of y’all never bin down South. I’m gonna tell you a little bit about it.’ I knew that they didn’t know what I was sayin’! But then, it was the feel of the music.”

24 April 2012

Take it to the bridge

Someone once asked the great songwriter Sammy Cahn – his name sits below titles on countless Sinatra records – the perennial question of his profession.

What came first? The music or they lyrics?

“The phone call,” he replied.

Song writing is hard graft. Only amateurs think its easy, the ones who have their eye on the quick money. They’re all over the radio, but few of their efforts will make it onto classic hits playlists. “Hack writers don’t get writer’s block and paradoxically, neither do hungry ones.”

That’s a line from Jimmy Webb’s book Tunesmith. It’s a primer about song writing. Most bookshops have them in their “making it in the music business” section. Strangely, they’re always written by unknowns. if they were that smart, or that hot, how did they get time to write about it? It seems, those that can, do; those that can’t, write “how to” books.

But Jimmy’s different. He’s the man who left the cake out in the rain, lost the recipe, and somehow made that dreadful image into a million seller, an unforgettable baroque pop epic. But I’ll forgive him ‘MacArthur Park’ and even his overblown performance in Auckland recently [1999]. To coin a phrase (and probably get sued), he’s a man who’s made the whole world sing.

My definition of a great song is something others want to sing, in the bath, at football, in the playground; one that nags you all day; one that continues to intrigue through an odd chord change, a crystal-clear image, a catchphrase that enters the language – or a cliché that finally gains substance when put to a melody: “your guess as good as mine”, “you always take the weather with you” …

The world has enough great singers, but not nearly enough great songwriters. Jimmy Webb’s Tunesmith wants to change that (and save us from those dire efforts that should stay inside notebooks). It’s an eccentric scramble of a book, given focus by the intensity of Webb’s purpose. The beauty is that it can be read on a technical or anecdotal level, and either way the result for the reader is inspiration (the hardest motivator to ignite).

Tunesmith reflects a lifetime’s obsession with song writing. It’s a big-hearted book that wants to share not just the lessons he’s learnt, but his passion for the art form. The advice ranges from pithy aphorisms and cautionary tales, to textbook talk about rhyme, narrative sense, collaboration, melodic rules and risks, plus cosmic stuff about creativity and even keeping your sanity. There’s also legal advice, about avoiding plagiarism and looking after your publishing. Somehow, he manages to both demystify the process and keep the magic alive.

But then there’s always a story to keep your head from going up, up and away. Like the executor of Cole Porter’s estate who licensed on of his songs for advertising use. He knew he’d blown it when he saw a TV ad for toilet cleaner, and heard the jingle: “I’ve got you … under my rim.”

Written for Aprap, the magazine of the Australasian Performing Right Association, 1999. Shortly before this, Webb performed in Auckland’s intimate Concert Chamber in a double bill with Dan Penn and Spooner Oldham. Song writing heaven, attended by every old music hand in town, though I didn’t hear this favourite:

20 April 2012

The Man from Turkey Scratch

And so Levon Helm passes from this mortal coil. The journey from Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, to the stages of the world – from seeing minstrel shows and Elvis in a tent, to being booed in stadiums – was like several lifetimes.

The Band always brought out the best in some music writers, and many had their obits waiting for Levon’s death a few hours ago from cancer, after a couple of days’ warning from his family. NPR has a swag of audio: archive programmes and past interviews. Rolling Stone has put some classic pieces on-line, including their 1969 cover story, and the great piece “A Portrait of the Band as Young Hawks” by Robert Palmer in 1978 (as a teenage saxophonist, he had played many of the same juke joints with the Hawks in the early 1960s). In it, Palmer evocatively describes Helm showing a teenage Robbie Robertson around his territory, the tiny town of West Helena on the banks of the Mississippi:

Levon Helm, the intense, wiry drummer who was to initiate him into its mysteries, met him at the Helena bus station and took him out to the Helm farmhouse, which was built on stilts to keep it dry during spring floods when the Big Muddy overran its banks. Levon's dad, a cotton farmer, told tales that made them split their sides laughing, and his mother cooked food that made them split their sides eating. Later, with Levon at the wheel, Robbie had a look at the town. There were black folks everywhere — he could remember seeing only a few in his entire life — and even the white folks talked like them, in a thick, rolling Afro-English that came out as heavy and sweet as molasses but could turn as acrid as turpentine if your accent or behavior were strange.

More on Levon soon. The photo above shows him at the drums, jamming near Woodstock with Robertson; it’s from the gatefold of The Band. Meanwhile, below is an 18-minute clip of the Band playing near their peak, live in Pittsburgh, November 1970, just after the release of Stage Fright. (Monitor: QUQ)

In other news, Leonard Cohen has been in court, confronting his former manager, who not only stole US $9.5m from him, but has been harrassing and threatening him for years via emails and texts. The New York Times reports that at the hearing Cohen said to her …

it gave him “no pleasure to see my one-time friend shackled to a chair in a court of law, her considerable gifts bent to the service of darkness, deceit and revenge,” and thanked Ms. Lynch “for insisting on a jury trial, thus exposing to the light of day her massive depletion of my retirement savings and yearly earnings, and allowing the court to observe her profoundly unwholesome, obscene and relentless strategies to escape the consequences of her wrongdoing.”

Even so, Mr. Cohen said he hoped that “a spirit of understanding will convert her heart from hatred to remorse, from anger to kindness, from the deadly intoxication of revenge to the lowly practices of self-reform.”

16 April 2012

Unsinkable

Like the Mutiny on the Bounty or the Kennedy assassination, the Titanic tragedy is a book publishing industry all of its own. There is even a Titanic app. The April 16 issue of The New Yorker considers the phenomenon, with an excellent piece by Daniel Mendelsohn. The subhead is “Why we can’t let go of the Titanic.” The one-word headline was so perfect I had to borrow it when blowing the dust off this review for the Listener from July 2011.

THE BAND PLAYED ON, by Steve Turner (UQP); AND THE BAND PLAYED ON, by Christopher Ward (Hodder & Stoughton).

When three of the musicians’ bodies were found several days later, bobbing among the icebergs, bandleader Wallace Hartley had his violin strapped across his chest. At his funeral, over 30,000 mourners crowded the streets of his Lancashire town, and his bandsmen were fêted as heroes. An orchestra of 500 performed a tribute concert at the Royal Albert Hall, conducted by Thomas Beecham, Edward Elgar and Henry Wood.

In anticipation of [this] year’s centenary, two books about the Titanic band have arrived simultaneously, with almost identical titles. Steve Turner, a popular-music biographer, concentrates on the band. Christopher Ward, a veteran newspaper editor and publisher, is the grandson of one of the musicians, so family comes first. Outwardly so similar, the books have differences that emulate the Titanic’s strict class structure. Turner is a stoker, working doggedly in the boiler room, while Ward is holding court in the first-class lounge, entertaining and enthralling with his family secrets.

As with the 1998 film version of this perennial story, there are clear heroes and villains. For both, the band can do no wrong. Turner’s villains are exploitative establishment figures such as White Star chairman Bruce Ismay (whose lifeboat seat was ensured) and the greedy booking agents who hired the musicians, lowered their pay and conditions, then charged their bereaved families for lost uniforms and sheet music. Ward unexpectedly keel-hauls his great-grandfather Andrew Hume: a violinist like his drowned son, Jock, but also a ruthless liar, bully and thief. Having driven his children from home with his regular beatings, Hume conned Titanic charities after the sinking and stole his granddaughter’s welfare grant.

Turner’s detective work exhumes fascinating details about the musicians’ lives, why they went to sea, and the importance of music in Edwardian society. On board the Titanic, the band and passengers had songbooks detailing 341 pieces that could be requested; musicians were expected to play waltzes, marches, airs, ragtime and opera selections.

Ward’s book is compelling, with a novelised style and a clear focus on the best stories. His details are sharp-edged: appalling musicians’ contracts; a vast shipping line that bills relatives to transport bodies home; a grand piano that crashes through walls during the ship’s sinking, crushing a steward. The “women and children first” concept came from the Titanic, he reports, and he manages to include a crew mutiny and a captain called Haddock. Ward’s family saga gets even more dramatic after the Titanic sinking, when Jock Hume’s sister takes revenge on their dreadful father.

George Bernard Shaw viewed the orgy of mourning over the Titanic and its band of heroes as “an explosion of outrageous romantic lying” – perhaps the final airs played by the band encouraged complacency, and a higher death toll. The musicians themselves, working to the end, didn’t realise until too late that there was no time for an encore.