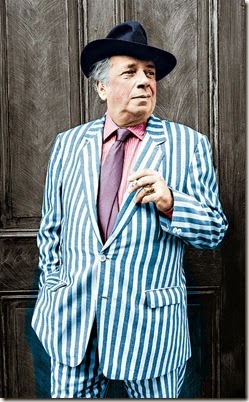

Inevitably, interviewing George Melly was an unforgettable encounter. That’s why I suggested it to the Listener. We met at 10.00am, he ordered a gin and tonic, and he was away. His 1965 memoir Owning Up about his days in a 1950s UK jazz band is one of the great music memoirs, about the days of touring before the M1 was built, staying in dodgy B&Bs with Carry On landladies, pints and pints of beer, and apres-gig knees-ups beneath the canal bridge. The article below was written in 1990, when Melly was one of many unfashionable musical guests of the “International” Wellington festival of the arts. I mean, were they serious about inviting Max Bygraves? But Melly’s talents went beyond the trad jazz they hired hiim for.

Fifteen years later, in 2005, I saw Melly wandering through a leafy street in St John’s Wood, London, very near Abbey Road. Two years before his death, he was still in his pyjama suit, but seemed decrepit with his stick and eye patch. All his memoirs are great reading, evening the final one about his physical decline, Slowing Down. He was trisexual – try anything – and he certainly tried. Was the Daily Mail pic serious when it captioned this picture, “Despite his bed-hopping, George Melly was loved by jazz fans across the world.”?

Melly, jazz singer and scholar, art critic and popular culture essayist, raconteur and bon vivant, still feels the pull of his birthplace. Immediately after his appearance at the 1990 International Festival of the Arts in Wellington he was going back to judge an art competition in a brewery. And the Liverpool Polytechnic have just awarded him an honorary degree.

Are they trying to make the man in the pyjama-striped suit and fruit-salad tie respectable? He hopes not. “It’s a great difficulty not to slip into being embraced by the establishment as one gets older. However the recent scandal about one’s seduction of Peregrine Worsthorne helps keep respectability from the door!”

Melly chuckles with saucy delight. The revelations in the defamation case between London Newspaper editors were in fact old news. Both Melly and the Sunday Telegraph editor had already written about their teenage liaison in their autobiographies. “But it was useful evidence in [Sunday Times editor Andrew] Neil’s trial of Worsthorne. Because Neil could say, ‘How dare this man say I shouldn’t go out with a perfectly respectable call-girl, and give her a Magimix, when he himself has admitted in print that he was seduced by a jazz singer!?’”

Surely Melly’s confessional memoir Owning Up makes it harder to be a victim of the tabloids? “I daresay they could find things that would embarrass me,” he says. “But it’s much harder. It’s not like I always pretended to be a pillar of the church and the establishment. You can’t accuse somebody of something they’ve already admitted to themselves.”

Melly arrived in London in the early 1950s, after a stint in the navy (detailed in Rum, Bum and Concertina). Although this was before it became a “positive bonus” to come from the provinces, he didn’t have any trouble infiltrating the London art world and music scene. “Liverpudlians take it for granted that they’re going to amuse and charm everyone, even if they’re not.”

An ideological battle was going on between jazz fans at the time. One was either a revivalist or a trad jazzer, and one didn’t fraternise with the opposition. They argued over the cut-off point when jazz lost its “purity” – after it left New Orleans, or when big-band-swing came along? Meanwhile the UK beboppers, led by Ronnie Scott and Johnny Dankworth, and better musicians, according to Melly, interpreted the jazz of their own era.

“i was a revivalist, totally,” he says. “I thought bebop was the work of the devil. Ridiculous nonsense. Nowadays one hears it as just a development, it came out of what came before it.” In the mid-1950s with the arrival of Elvis, it looked as though jazz was doomed. “But somehow it staggered to its feet and produced its most banal and boring period, the trad boom of the late ’50s, which in turn was swept out of the way by the Beatles: beat music, as we called rock’n’roll.”

Melly is adept at giving a potted history of post-war British jazz, having witness its “death”, and revival, several times over. For the moment, he says, jazz is “extraordinarily chick” in London, even if it sounds like an accessory to fashion photography. Young black musicians like Courtenay Pine are stars, jazz has replaced rock on film soundtracks, and is used to advertise clothes and scent. “You see people in pseudo-Armani black clothes and pale expressionless faces listening to that form of jazz. I don’t know them very well, these types of people. I’m more likely to see them at art galleries than at a jazz concert.”

In the 1960s, Melly retired from singing and started to write. Revolt Into Style, his 1970 collection of essays on British popular culture, still reads well, relying on sober, informed analysis rather than dated hipness. The book almost predicts punk rock with its conclusion that pop was “temporarily done for”, having turned “pretentious and sour”.

For a recent new edition. all Melly added was an afterword saying that punk was the only exciting thing to have happened since. “But I said I was letting the book stand. As a consequence there are now what appear archaic references, and the word negro throughout, which now gives one a shock to read. But the word was respectable then – if I’d used black I would have been very unpopular. And now I believe ‘black’ is dying out and one has to say something cumbersome like Afro-American.”

Melly returned to performing in the mid-1970s, with John Chilton’s Feetwarmers. “I still did it when people asked me, but they very infrequently did during the Beatles.” Ronnie Scott’s club gave them a residency because, he suspects, they attracted a crowd of young heavy drinkers, and the act became a cult. It was time to give up the day job. “We decided to go back on the road, we’d had a taste of it again. And it promised to be in rather more luxurious circumstances than hitherto. in the ’50s one led a very squalid life, which appeals to you when you’re young, but less so when you're middle-aged.”

Is performing still, as he once suggested, like seduction? “Yes, but I’m rather better at performing than seduction, I have to add. But it’s a similar process. I have an audience there who is a virgin every night, willing or unwilling. You come on stage and have to get them into a state where they’re saying ‘yes’ by the end. The similar may appal some people but I think it’s an accurate one – and for every performer, in whatever sphere. Playing the cello with an orchestra, acting Richard III, the audience has to be seduced.”

“Of course, right from the start one questioned one’s right in black music. I did it at first because I so believed in it, and I’ve done it for so long I can’t give it up. And I must say what criticism I’ve had has always been from white critics. And I’ve sung with many black artists, none of whom have been anything but … kind.”

Melly’s love of 1920s jazz began at school, when he heard Muggsy Spanier’s ‘I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate’. “In between seducing Peregrine Worsthorne I was listening to this music,” he says. Then, the musicians were still in the entertainment business and consequently “produced a great deal of marvellous music because they weren’t self-consciously in pursuit of great art. There is high art, there is low art, and there is an awful lot of art which is pretentious, takes itself terribly seriously and produces nothing of lasting value.”

Bessie Smith is till his number-one singer. Next, he’d put “a whole lot of people in a row”: Ma Rainey, Jimmy Rushing, Joe Turner, Fats Waller, the “underrated” Ethel Waters, Bill Holiday. “There’s a big spectrum there, but Bessie – not even Billie has the same effect on me.”

However Melly no longer sings ‘Frankie and Johnny’ – the seduction requires too much energy. “One has to pretend to be shot – if possible fall off the stage, which is sometimes several feet high – leap to one’s feet and continue to sing, and so on. I don’t think I’d be able to do it more than once, and then with luck. So I dropped that many years ago.”

Another singer who made ‘Frankie and Johnny’ his own was Sam Cooke, who was shot in circumstances uncannily similar to those in the song Melly the scholar hasn’t considered this example of life following art. But if that’s the case, he say’s, “I’d prefer ‘Do You Want a Hot Dog in Your Roll’, which is a song I sing now, to come true than ‘Frankie and Johnny’.”