Pilgrim’s Progress

The Return of Robbie Robertson, 1987

“Robbie Robertson found himself soon after he dropped Jaime from his name. As a guitar player, he ranks high among the world’s top dozen. As a songwriter, he’s more of a storyteller than a poet. He narrates the changing times, the soul of history. But it’s more as a producer that Robertson’s full range of curious talent will ultimately be expressed. Whether in music or in films, or a combination of both, you can bet that Robbie will someday produce a masterpiece all his own.”In the early days of the Band, Robbie Robertson wrote a song called ‘Get Up Jake’. It told the story of a man so lazy that the whole town would show up to watch him get out of bed. In 1970 came Stage Fright with ‘Sleeping’, a song Robertson wrote with Richard Manuel: “To be called before noon / is to be called too soon … I spend my whole life sleeping.”

(Emmett Grogan, “The Band’s Perfect Goodbye,” Oui, May 1977.)

Since the Band called it quits with the Last Waltz concert on Thanksgiving Day, 1976, Robbie Robertson has been hibernating.

In the past decade, only the occasional soundtrack compilation and a cult film Carny have shown that one of the finest songwriters in rock music was still active.

But late last year, Robertson repaid those who kept faith in him with the appearance of his first solo album. Robbie Robertson is a powerful album that updates his music with the Band. The album’s heartland adventures and fables on the American condition with a sound as contemporary as a silicon chip. It could be the work that Emmett Grogan predicted a decade ago.

But late last year, Robertson repaid those who kept faith in him with the appearance of his first solo album. Robbie Robertson is a powerful album that updates his music with the Band. The album’s heartland adventures and fables on the American condition with a sound as contemporary as a silicon chip. It could be the work that Emmett Grogan predicted a decade ago. However speaking from Los Angeles last month, Robertson says his first solo album wasn’t like an albatross hanging over him all the time: “It wasn’t like the album, the album … the songs just weren’t there. But slowly they started to emerge and I thought, hey – there’s an album here.”

He grudgingly admits that this album is a return. “But I never thought of it like that. I just had the opportunity to not have to make a record, to get out of the album/tour syndrome. A lot of people from my generation continued making records, and a lot of them sounded very medium to me. And I thought, if you just don’t have an opportunity to recharge your battery or re-shuffle the deck, it’s harder to just keep pounding the them out.”

Record making, he says, had stopped being “a creative process” for him – and that’s understandable. After years scuffling round the bar band circuit as the Hawks, then going through trial-by-fire supporting Dylan as he went electric, the Band began recording in 1968. The quickly produced two certified masterpieces – Music From Big Pink and particularly The Band (though I’d argue that the smoother Stage Fright warrants consideration). These albums said, really, all they wanted to say.

But from 1970 on, the Band trod water, sustained by the efforts of Robertson, who by then had become the group’s sole songwriter. “I don’t know why the others weren’t writing,” he says. “I would try and harp on at them, but didn’t get anywhere.”

Their 70s work had its moments though: Rock of Ages caught them blazing at their performing peak, aided by New Orleans horns. Moondog Matinee, a personal jukebox of tunes they’d cut their teeth on as teenage rock’n’rollers, has more verve and depth than most such projects, and Robertson always managed the odd song (‘It Makes No Difference’, ‘Ophelia’, ‘Christmas Must Be Tonight’) that approached the halcyon days of ‘The Weight,’ ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’, ‘King Harvest’ and ‘The Rumor’.

The songs were vignettes of American history, frontier legends filled with characters, with music full of character: the swagger of rock’n’roll, rollicking R&B, the earthy funk of Southern soul, the stories and heartache of country … all mixed together with a bubbling spontaneity, each member whooping out interjections with exuberance. This was group music, played exquisitely by musicians who, as Ed Ward has written, had earned the right to be known simply as the Band.

The Band, at the time of Music from Big Pink, upstate New York, 1968. From left: Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson and Robbie Robertson.

The Band, at the time of Music from Big Pink, upstate New York, 1968. From left: Rick Danko, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson and Robbie Robertson.Since Dylan’s motorbike accident in mid-1966, the group had been holed up like the James Gang in the wooded hills of upstate New York, writing songs and playing together in sessions that would eventually appear as The Basement Tapes. When Big Pink came out, word quickly spread about the Band by a buzz of musicians and critics rather than a publicist’s blitz (though in 1970 they somehow made the cover of Time).

Among the converts were George Harrison and Eric Clapton who, sick of psychedelic indulgence, wrote the mellow ‘Badge’ together. Harrison visited the Band in late 1968 and came home raving about them to his fellow Beatles, who were going through their own rootsy ‘Get Back’ phase.

“Ringo would go down a bomb,” Harrison can be heard exhorting the others on Let it Be outtakes. “Their favourite track on the [White] album was his, because that’s their scene, living up in the woods, just singing their songs. The reason all those people are singing different lines is they all want to be the singer. They’re all singing together, but it gets like discipline, where nobody is crowding anybody else out. You dig, baby?”

Replies Paul: “Looks like rain, doesn’t it?”

But that’s history, and one thing Robertson didn’t want to make was a Band LP. “I couldn’t without the Band,” he says. “So I just did what comes natural to me now. I didn’t try to make a modern record – there are no Fairlights or Synclaviers on it, mainly guitars - this is just the way I’m making music now, the way I’m hearing it now. I hope it’s like some of the other work I’ve done, I hope it’s as timeless, that it doesn’t matter when it came out.”

Robbie Robertson is a record that has been crafted for the CD age. Robertson enlisted Daniel Lanois to co-produce, and not only is the influence of the man behind Peter Gabriel and U2’s recent albums crucial, but those two artists make distinctive contributions to several songs.

Apart from the Gabriel/U2 flavour to some tracks, and cameos by ex-Band colleagues Rick Danko and Garth Hudson on a couple, the musicians on the album are chosen for their unique styles rather than their high profiles. “I didn’t want to get in the usual bunch of sessioneers that would make everybody say ho-hum,” says Robertson. “I like musicians who bring something new and of themselves to the project, who help you get the sounds you want.”

Among them was fellow Canadian Bill Dillon who, like Robertson, spent his apprenticeship playing for rockabilly roustabout Ronnie Hawkins. Manu Katche is a French drummer whose subtle style complements bassist Tony Levin; both have played for Peter Gabriel. Contributing backing vocals are the BoDeans, Ivan Neville from the first family of New Orleans funk, and Lone Justice’s Maria McKee.

The dominant voice however is Robertson’s though the melodies are itching for some of the Band’s carefree vocal banter. Although he wrote the bulk of the Band’s songs, Robertson had only sung lead twice during their heyday. Everybody had their own job to do in that group, he explains. “If I had been writing the songs, playing lead guitar and doing the singing, it wouldn’t have been a band anymore. Now that I don’t have those guys around all the time, I don’t have nay choice but to sing my songs.”

Robertson has always regarded himself as a storyteller, avoiding writing songs from a personal point of view. “I never felt I’d experienced enough,” he says. “I thought I was too young to be writing about myself.”

On Robbie Robertson the evocative mythology of his earlier writing remains, but with a difference: for the first time Robertson reveals his Indian background. His mother was Iroquois, his father a Jewish professional gambler. The summers of his childhood Robertson spent on the Six Nations Indian reservation above Lake Erie, where from relatives playing mandolins, fiddles and guitars he heard his first music.

“It didn’t seem appropriate to write about my Indian background with the band,” he says. “I didn’t feel I could take a song to them and say, ‘Hey guys, this is the theme that’s running through the album – it’s about an Indian …’

“Now I’m making my own records I can say what I like.”

With the confused draftee in ‘Hell’s Half Acre’, the symbolism of ‘Broken Arrow’ and the spiritual outlook towards the nuclear threat in ‘Showdown at Big Sky’, Robbie Robertson paints panoramic images of the Indian in the 20th century. What’s happened to the Indian is a tragedy for us all, he says.

“There was something in that lifestyle, the simplicity and beauty of it – so right in tune with nature – that was priceless. On ‘Big Sky’ I was thinking about the simplicity of that Indian life- true to the earth, to the sky and to the elements – and here we are playing with it, rolling the dice every day.”

The maternal link between humanity and the land has been a constant theme in Robertson’s writing, however, and that’s why his songs have always seemed as apt to New Zealand’s rural culture as the folklore of novelists Ronald Hugh Morrieson, Barry Crump or John Mulgan. Take The Band’s ‘King Harvest (Has Surely Come)’, a powerful Grapes of Wrath saga about dustbowl farming and union corruption. ‘Dixie Down,’ while a three-minute history of the Civil War, has a line that seems to reflect the Indian attitude to the land: “I spent my life chopping wood … You take what you need and you leave the rest / But they should never have taken the very best.”

The maternal link between humanity and the land has been a constant theme in Robertson’s writing, however, and that’s why his songs have always seemed as apt to New Zealand’s rural culture as the folklore of novelists Ronald Hugh Morrieson, Barry Crump or John Mulgan. Take The Band’s ‘King Harvest (Has Surely Come)’, a powerful Grapes of Wrath saga about dustbowl farming and union corruption. ‘Dixie Down,’ while a three-minute history of the Civil War, has a line that seems to reflect the Indian attitude to the land: “I spent my life chopping wood … You take what you need and you leave the rest / But they should never have taken the very best.”A personal digression to stretch the point. After growing up to The Band, one summer while revelling in Greil Marcus’s Mystery Train – which features a masterly critique of their work – I took a job at an abattoir. In my locker I found Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, the gripping study of Indian oppression. An elderly Maori slaughterman asked me what I was reading. A history of the American Indian, I said, how the land was like a mother to them, that they never exploited but always respected, they just took what they needed to stay alive. Then the settlers and soldiers came in, decimated the tribes and devastated the land.

“Just like us,” he replied.

How did Robertson react to Greil Marcus’s interpretation of his music – did he think it was accurate?

“When I read it, I thought it was brilliantly written and very entertaining. Often I’d think, ‘Yes, that’s it – he’s got to the heart of it.’ But sometimes I didn’t know what he was talking about. You read what some people put onto your music and it bears very little relation to what you wrote.”

The element of mystery has always been important to Robertson. Years ago he said, “I learnt the words to Little Richard’s songs the best I could. What I couldn’t figure out, didn’t matter.”

Now, he talks about the Shadowland. “It’s just a name I have for the place where the stories come from,” he explains. “I got this idea that I could see this place, and I was playing the part of the storyteller … and as this picture because clearer, the music started to come to me. Then I got real serious about writing the songs.”

‘Somewhere Down the Crazy River’ is a Chandler-esque fable about coming-of-age inspired by Robertson’s first visit to the Mississippi Delta as a 16-year-old. ‘Broken Arrow’, the album’s most effecting moment, is an earthy love song that relates to his Indian upbringing. ‘Fallen Angel’, the celestial opening track with Gabriel’s ethereal vocal, started out as a song about good and evil.

But as the prayer-like quality of ‘Fallen Angel’ evolved, so too it emerged to Robertson that he was writing about Richard Manuel, the Band’s tortured pianist with the huge heart and heavenly voice (‘I Shall Be Released,’ ‘Whispering Pines’) who hanged himself in 1986.

“I had this mood going in it, this heartbeat and crying vocal sound, and it was a little reminiscent of things Richard would do,” Robertson says. “It became more and more personal, and very apparent that I was writing the song for Richard. It made me feel good that I could do this, but it was hard – sometimes I’d be fine working on it, sometimes it tore me apart.”

Another constant thread through Robertson’s work has been his Biblical references: the frontier evangelism of ‘Caledonia Mission’ and ‘To Kingdom Come,’ the Faustian walking-with-the-Devil of ‘The Weight’ and soul-selling fo ‘Daniel and the Sacred Harp’. The religious imagery continues on Robbie Robertson:

“The Bible is such a wonderful book, full of great stories,” he says. “It’s very well written – a great resource. I’ve always been a sucker for that stuff, and always will.”

What of the 80s’ puritans, taking the name of the Bible in vain? “I never think about them. They’re clowns.”

During his decade-long hibernation, Robertson dabbled with the film world. The success of The Last Waltz – Martin Scorsese’s film of the farewell show that is the concert movie by which all others are judged – led to several other projects. In Carny Robertson indulged his love of the travelling carnival world, producing, writing, scoring and acting. As a child, he worked in a carnival, and indeed his language is still dotted with the hustler’s colourful jargon.

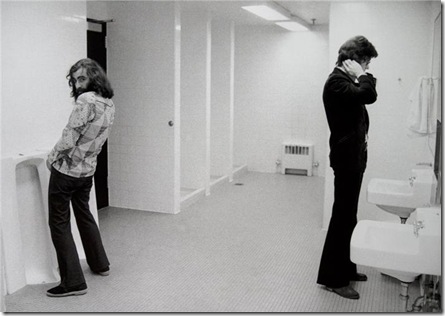

But that was his only acting role; soundtracks for Scorsese’s Raging Bull, King of Comedy and The Colour of Money followed. Even before The Last Waltz Scorsese knew the Band’s work intimately; afterwards, he and Robertson became firm friends. (They are pictured here at the time of King of Comedy.)

“I thought it was fantastic the way [Scorsese] used music in his movies. It runs right through his work, the film Elvis on Tour he did, Woodstock he edited, then Mean Streets and Taxi Driver. That’s why I asked him to do The Last Waltz – I felt this guy really knows, he understands what music is all about.”

Robertson expresses some ambivalence to music videos, disliking the artificiality of directors such as George Miller (Mad Max, The Witches of Eastwick) in favour of a more realistic approach. (His favourite music film is the classic The Girl Can’t Help It; his favourite score, Alex North’s for A Streetcar Named Desire.)

But Scorsese, who filmed Michael Jackson’s ‘Bad’ video, has just completed a “brilliant” clip for ‘Somewhere Down the Crazy River’, says Robertson. It stars Maria McKee. “As long as videos are done properly, great,” he says. “But so often they’re done cheaply, or indulgently – as if someone’s just got a camera, and they want to use every trick they can. Then you get away from the music.”

Having got the urge to make another album in 1983, Robertson worked on it at his usual snail’s pace. Once started, production stretched to 18 months – and costs to a million dollars. The music industry was starting to make Heaven’s Gate allusions. Consequently, the promotion machinery is in full gear and Robertson’s profile is high. He has played live on The David Letterman Show and Saturday Night Life, and now a tour is planned with musicians who played on the album.

Now that the urge to write has returned – how long until the next album?

“I’m on a roll now,” he says. “Once I get the tour out of the way, I’ll start thinking about it. It won’t be long.” As he sings on ‘Testimony’: “Bear witness, I’m wailing like the wind. Come, bear witness, the half-breed rides again.”

© Chris Bourke - first published in Rip It Up (New Zealand), April 1988.

2011: I have been a little hesitant to post this as 23 years on I feel a little suckered in by the son of a professional gambler. A big Band fan since childhood, I have never been so excited before a phone interview as this one. At the time, the album was state of the art and seemed to have some heart. Robertson’s portentousness was forgiven by those of us so pleased to see him back with something new. Much of the press, Greil Marcus observed, was fawning, and perhaps this is an example. (He then went on to say Robertson’s follow-up, Storyville, was better: something I’ve never agreed with, outside the great ‘Soap Box Preacher’). This interview was less than two years after the tragic suicide of Richard Manuel; the revelations of how Robertson (and Albert Grossman) allegedly manoeuvred the song publishing of the Band, shutting the others out, were still to come. The evidence of self-importance is certainly there in The Last Waltz, though it continues to deliver. But when people accuse a bandleader of poaching the songwriting credits, I always think: where are the songs you’ve written since? None of the others came up with much new material in the 33 years after Islands, the group’s patchy, contract-fulfilling last album.

After his 1987 return, Robertson became comparatively prolific, with two albums around Native American themes. They weren’t especially successful as music or merchandise, and his collaborators may have been left feeling that they’d been carpetbagged by a “charming hustler”. That’s the way I referred to Robertson in a 1994 interview – and first-hand anecdotes support this view –but his shtick doesn’t take away from the enduring rewards of the Band’s classics. Also, he has Scorsese’s imprimatur. A few days ago word came of a new Robertson solo album due in April, and by the sound of this advance song, released on the net, it’s a return to basic songwriting (with paint by numbers lyrics). How to Become Clairvoyant may feature a tribe of celebrity cohorts (Clapton, Winwood, Trent Reznor), but lacks the cathedral-scale sonics that contradicted the Band’s ethos. To lighten things up, here’s a pic from the excellent roots/country rock/Americana website When You Awake:

Richard Manuel checks his fly, while Robbie Robertson checks his hair. A scene in the men’s room in Denver during the Bob Dylan tour of 1974, photographed by Barry Feinstein.

No comments:

Post a Comment