A Mississippi Journey, 1989

Part two of a six-part series. Part one here.

Memphis in the Meantime

Memphis has so much history, they don’t know what to do with it. Once the city was notorious as a rough-and-tumble frontier-town, a haven for Mississippi flatboatmen wanting to party on their way down to New Orleans. Now, immortalised for nurturing the blues and rock’n’roll, it is a musical Mecca legendary for Beale Street, the Sun Studios and Stax Records.

Musicians around the world have sung about going to Memphis, falling in love there, leaving it, or not being able to get a f1ight.

Chuck Berry wanted long distance information to give him Memphis, Tennessee. The Rolling Stones met a gin-soaked barroom queen there, and Little Feat a Southern belle under a street lamp. Paul Simon was drawn to Graceland. Meanwhile Bob Dylan couldn’t make it, being stuck in Mobile (Alabama) with the Memphis blues again.

These are just the most obvious examples. But when you see the position of the city, it’s easy to understand why it’s been so romanticised. Situated just 400 miles north of New Orleans, it’s a gateway to the South, or out of it. You can get there by boat on the Mississippi, or by driving along Highway 61. Or go by rail, using the same route thousands of Southern blacks took when migrating north to St Louis and Chicago, taking their blues and jazz with them. That train is called the Midnight Special, and I feel another song coming on.

The locals are at once bemused but respectful of their heritage. When they talk of the Elvis phenomenon, they separate the music from “the deity.” The former revolutionised the world, the latter draws 1.5 million visitors to Graceland each year. Underground musicians who revere more contemporary local heroes such as Alex Chilton relate with affection anecdotes about living legends. “I bumped into Al Green last week at Ardent Studios, talking to Willie Mitchell. Manic as ever.” “Did you hear Jerry Lee’s neighbours complained again? He keeps shooting off guns in his fancy apartment.”

During the heyday of Beale Street, Memphis was known as the “murder capital of the US.” A police station on the street contains a museum that recalls the lawlessness that went with the saloons, casinos, brothels, and pawn shops. One gets the feeling that the only problems the police deal with now are lost tourists. For Beale Street, like much of America that has a past, has been “historified.” Anything still standing from its sordid past has received a lick of paint and a bronze plaque. There are statues of Elvis and W C Handy, and the barrooms have been renovated into chintzy but still funky juke joints.

“It was the greatest place on earth,” said an old blues musician, “until they rurnt it.” But some symbols still remain untouched. Schwab’s department store is like a five-and-dime from the age when things did cost five or ten cents, and you can still find on its chaotic shelves voodoo powders, magic potions, clerical collars and handcuffs. And across the street stands Lansky’s Menswear, the place Sam Phillips of Sun Records sent Elvis Presley to learn how to dress cool (ie, like a black man). In the window are some striped winklepickers and a yellow suit with leopard skin lapels.

Graceland is a 10-minute drive south, down Elvis Presley Boulevard, and also a moving experience. The patter of the guides is sterile and bored; 4000 teary-eyed fans will pass before them today. But shuffling through the rooms stuffed with lurid furnishings and grotesque fittings, all in the best veneer money can buy, you realise Elvis simply had no idea – of how to handle his wealth, his fame, or his talent.

An alternative view of Memphis is provided by the black history tour, whose militant guides give the details usually left out by the publicists. They point out a statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, the Confederate general who is revered by whites but hated by blacks. A brilliant cavalry leader who developed guerilla warfare, he later founded the original Ku Klux Klan. He also ran a slave farm, keeping his strongest slaves in cages for breeding.

They explain why Memphis, unlike most of the other major US cities, has never had a black mayor. There is no one area of black housing, but many scattered pockets, all producing their own candidates and splitting the vote. It’s a town planning legacy of Edward H “Boss” Crump, the man who dominated Memphis politics for nearly 50 years earlier this century. Blacks were allowed to vote; Crump’s machine told them who to vote for.

Despite the billion dollars that has been spent on redeveloping the city in the past decade, downtown Memphis has a ghostliness about it. Grand old buildings stand empty as businesses and their customers have moved out to the suburban malls. The city has turned its back on the Mississippi, once the lifeblood of its economy. Half of the US cotton crop still goes through Memphis, but it leaves by train, and the cotton warehouses facing the river are being turned into yuppie apartments.

“Start something great in Memphis” is the slogan of the city’s publicists, an appropriate line considering the city’s impact on Western culture. We have all, as local writer Stanley Booth points out, shopped at supermarkets, eaten at drive-in restaurants, slept in Holiday Inns, and heard blues, rock’n’roll and soul because people in Memphis found ways to convert these things into groceries. Now the city has decided tourism will be its saviour. The complex on Mud Island, with its Mississippi museum and magnificent working scale model of the river, is a step in the right direction.

The problem Memphis faces is living up to all its history, and making it work for the city, tastefully.

*

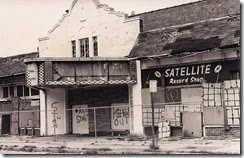

Twenty-four years later, this article has of course dated. Saying it had so much history, but didn’t know what to do with it, was a reflection of locals I spoke to who did know what the place had to offer, but despaired at the lack of initiative taken to celebrate that; or that what had been done was in a corporate way missing the soul. Since then, there has been a lot of regentrification and redevelopment of the downtown area. There are also museums devoted to Stax (reconstructing the original building, seen above just before it was demolished in 1989) and, on Beale Street, Memphis rock’n’roll. Perhaps the city’s establishment and its attitude towards music and other elements of its history has changed, but race and class are barriers that don’t evaporate easily, and buildings of architectural or cultural value are always under threat. Last I heard, Jacqueline Smith was still going strong, 24 years on. Historic Memphis is an excellent non-sanitised site to explore. A pioneering alternative view of the city’s pop culture is former Shangri La Records’ proprietor Sherman Willmott’s Low-Life Guide to Memphis tours. Local music writer Robert Gordon is about to follow up his classic 1994 book on the city’s underground music It Came From Memphis with what is likely to be the best book on Stax, Respect Yourself, and early 1980s psychobilly star Tav Falco has written a fascinating history of lowlife Memphis, Ghosts Behind the Sun. Thanks to David Nicholson of the Memphis Convention and Visitor’s Bureau, who after I cold-called him was tireless in his efforts to help, though he probably wondered if I was legitimate. Once he heard where I was staying – a hostel that was dis-affiliated from the YHA, the owners seemed to resent the guests, and there was one toilet for 17 people – he shuddered and sorted out a room at the Sheraton, and drove me around town sharing the insights of a Brit who had lived there for eight years. The visitor’s bureau has a great website with much more recent articles on things like Memphis and civil rights, black history, its music legacy and current status (eg Justin Timberlake, Amy LaVere), its entrepreneurial history, film-making, food, bars, etc.

It would be wrong not to include this very 80s clip of John Hiatt at Fisk University, Tennessee, with many guests including Carl Perkins, Rodney Crowell and what looks like the Jordanaires.

No comments:

Post a Comment