It’s a public holiday today and the Boss is working on a dream. Bruce Springsteen has a new album out of that title and ... am I still interested? Well I’m at least intrigued, even if I think his last classic was 1987’s Tunnel of Love and I couldn’t get through more than a couple of listens to 2007’s bombastic Magic (the curse of over-compression did not make it easy). But sceptics would have to admit that this made a stunning spectacle, even if Archie at Word quipped drummer “Max Weinberg has let himself go, hasn’t he?”

It’s a public holiday today and the Boss is working on a dream. Bruce Springsteen has a new album out of that title and ... am I still interested? Well I’m at least intrigued, even if I think his last classic was 1987’s Tunnel of Love and I couldn’t get through more than a couple of listens to 2007’s bombastic Magic (the curse of over-compression did not make it easy). But sceptics would have to admit that this made a stunning spectacle, even if Archie at Word quipped drummer “Max Weinberg has let himself go, hasn’t he?”

When Springsteen finally made his visitation to New Zealand in 2003, I was asked to write a piece marking the occasion. After delivery the editor said, “Well I like it, though it’s a bit grown-up for us.” He had obviously been spared the agony of reading academics write about pop; treatises like The Dialectics of Bruce that always seem to miss out the music.

The 2003 concert was stunning, everything you’d hope for after a 25-year wait, despite the rain that bucketed down for hours beforehand. I don’t think that was the only reason the audience size was one quarter (25,000) what it would have been if it had taken place in 1985.

Using NPR’s “first listen” facility, Working on a Dream sounds like a return to form, with subtle gems I’ll keep returning to (the country shuffle of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ and the folkie ‘Last Carnival’), only one meat & spuds bash (‘My Lucky Day’), and some great lines, such as the title ‘Queen of the Supermarket’ and ‘The Wrestler’s weary “if you’ve ever seen a one-trick pony / then you’ve seen me.”

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO BRUCE

By Chris Bourke, 2003

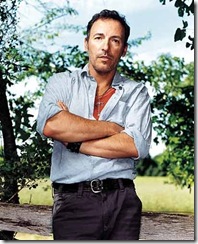

When Bruce Springsteen put his E Street Band back together in 1999, he was on a mission from God. In the 1970s, his concerts had climaxed with a rollicking “I’m just a prisoner of rock’n’roll” routine; now he returned older, wiser and a little battle-weary. He no longer leapt from the top of the grand piano, but stepped down cautiously. His limp is a war wound received not in Vietnam – though he has written movingly of his shell-shocked generation – but on stage.

When Bruce Springsteen put his E Street Band back together in 1999, he was on a mission from God. In the 1970s, his concerts had climaxed with a rollicking “I’m just a prisoner of rock’n’roll” routine; now he returned older, wiser and a little battle-weary. He no longer leapt from the top of the grand piano, but stepped down cautiously. His limp is a war wound received not in Vietnam – though he has written movingly of his shell-shocked generation – but on stage.

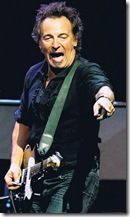

Springsteen returned with a new closing persona: he was now a rock’n’roll preacher. While the band vamped on ‘Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out’, he paced the stage bent over, testifying, all but speaking in tongues. He cried, “Tonight I want to throw a rock’n’roll exorcism! A rock’n’roll baptism! A rock’n’roll bar mitzvah!”

Ten years earlier, Springsteen and the E Street Band had gone their separate ways; it was a rare example of a boss handing in his notice. They may have conquered the world during the reign of Ronald Reagan, but this gang of New Jersey wide-boys had bonded in the era of Richard Nixon.

It was a simpler world. Nixon opened up China, and Reagan quipped he would start bombing Russia in five minutes. In 1999, with the US economy booming under Clinton, and no overt enemies, offering a rock’n’roll salvation to all colours and creeds made sense, especially to an old ham like Bruce Frederick Springsteen, lapsed convent schoolboy of Freehold, NJ.

Two years into the reunion tour, though, things changed. Springsteen lives a couple of hours’ drive from Manhattan, but as the crow flies his New Jersey farm is only about 30 km from the site of the World Trade Centre. He used to see the Twin Towers peek through the haze while driving near his home, so the attacks literally altered his horizon; they also devastated his community. His farm is in Monmouth County, where 158 people lost their lives: the largest cluster of victims in New Jersey.

In his neighbourhood over the following weeks, he noticed the constant funerals taking place in local churches. There were candlelit vigils and benefits, and Springsteen took part in a few. In the communities of the eastern seaboard he is a virtual poet laureate; many of the obituaries mentioned the victims’ love of his music, so he telephoned their next-of-kin to offer condolences. His children and their classmates express their fears about terrorists, and Springsteen himself has compared the atmosphere to the Cuban missile crisis of his childhood.

Once, Springsteen worked in only one gear: full-throttle optimism. There may have been darkness on the edge of town, but those streetwise Johnnys flashing flick-knives on the boardwalk were really posers out of West Side Story. Life was a panoramic movie, and all the classics he caught in fleapit theatres seemed to inspire elegiac songs: ‘Prove It All Night’, ‘Badlands’, ‘Thunder Road”, ‘All That Heaven Will Allow’.

But during the Reagan years, the “runaway American dream” turned sour; the boardwalks were cluttered with the homeless huddling in cardboard boxes. He watched The Grapes of Wrath, listened to Woody Guthrie, and made connections with the streets that were getting meaner. The songs of Nebraska were cinema-verité documentaries, unrelentingly bleak-and-white.

Reagan misunderstood Born in the USA when he quoted it during the 1984 election campaign; on the album’s cover shot, Springsteen is either walking on the flag or urinating on it. But in the mid-1980s the aspirational fantasies of Springsteen’s songs came true for their author. Suddenly, after years as a cult bohemian waif from “Joisey” , he was Bruce Superstar; he may not have worn his Y-fronts outside his trousers, but his bandanas were in red, white and blue.

The new, buffed-up Bruce worried the cultists: those bandanas seemed to push his eyes closer together and lower his brow. Now a rock star, he married a model; the liaison didn’t work out but the album from this period contains some of his finest writing. Unlike its predecessors, Tunnel of Love isn’t drunk with words; it’s low on dramatics but full of drama. The music is austere, and so is the imagery:

“Woke up this morning the house was cold

Checked the furnace she wasn’t burnin’

Went out and hopped in my old Ford

Hit the engine but she ain’t turnin’

We’ve given each other some hard lessons lately

But we ain’t learnin’ ” (‘One Step Up’)

He fell in love with his backing singer Patti Scialfa, a genuine “Jersey girl” who had infiltrated the boys’ gang. Springsteen, who adores his Italian mother but had a troubled relationship with his Irish-Dutch father – resolved before he died in 1998 – finally settled into family life. The 1992 album Lucky Town opened with a song called ‘Better Days’:

“These are better days baby

Better days with a girl like you …

Well I took a piss at fortune’s sweet kiss

It’s like eatin’ caviar and dirt

It’s a sad funny ending to find yourself pretending

A rich man in a poor man’s shirt”

The uncluttered writing revealed his influences, like footnotes in a self-education programme: the hard-boiled fiction of James M Cain, the Southern gothic stories of Flannery O’Connor, the working-man’s blues of Hank Williams and Merle Haggard. His starkest album The Ghost of Tom Joad (1995) took its name from The Grapes of Wrath hero, and its content connected with author John Steinbeck’s social activism.

Worthy, said the critics; dull, replied the common man. Tom Joad was folk music to which one couldn’t dance in the dark. Two touching songs from films restored him to the airwaves: ‘Streets of Philadelphia’, about the AIDS crisis, and the ballad ‘Secret Garden’. With the return to epic, switchblade rock on ‘Murder Incorporated’, the journey back to the E Street Band was underway.

In the Al Bundy-meets-Al Green preacher routine of the reunion tour, he suggested salvation would come not through God, or the afterlife, but from within – and from reaching out to those nearby. When September 11 occurred, he was in the right head space to cope with it in his writing. He has been closing recent shows not as a pentecostal preacher but with two songs written before the attacks: ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’ and ‘My City of Ruins’. The latter is actually about the economic renewal of his beloved beach town Asbury Park, but it seemed more suitable to play for the victims’ telethon after September 11 than ‘Into the Fire’, one of the songs written as the horizon changed shape.

In the Al Bundy-meets-Al Green preacher routine of the reunion tour, he suggested salvation would come not through God, or the afterlife, but from within – and from reaching out to those nearby. When September 11 occurred, he was in the right head space to cope with it in his writing. He has been closing recent shows not as a pentecostal preacher but with two songs written before the attacks: ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’ and ‘My City of Ruins’. The latter is actually about the economic renewal of his beloved beach town Asbury Park, but it seemed more suitable to play for the victims’ telethon after September 11 than ‘Into the Fire’, one of the songs written as the horizon changed shape.

Springsteen describes ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’ (which is pointedly followed in concert by a down-beat ‘Born in the USA’) and ‘My City of Ruins’ as “gospel songs”. And when he heard that the Italian translation of the hymn-like title of his new album The Rising was “La Resurrezionne”, the theme of redemption was in place. A priest friend of Martin Scorsese once allegedly said, “Marty – too much Good Friday, not enough Easter Sunday!” But the Jesuits would be happy with the vocabulary of Springsteen’s song titles in recent years: ‘Souls of the Departed’, ‘My Beautiful Reward’ and now ‘Paradise’. You can kick a boy out of the convent, but you can’t kick the convent out of a boy.

A third of the songs in Springsteen’s recent shows come from The Rising (a strong album, if no classic). ‘Mary’s Place’ is the crowd-pleaser that most recalls the exuberant celebrations of the early E Street Band, where burlesque rhythms, a honking sax and suspended chords combine to tease the audience to ecstasy. A party is getting underway, the rug has been rolled back and the record player is up loud. But in the window burn seven candles, presumably for loved ones recently lost. “My heart’s dark but it’s risin’ / I’m pullin’ all the faith I can see.” This is no mindless celebration, but a resurrection of the soul.

© 2003