Finding an excellent recent podcast of a concert by Southern songwriter Dan Penn accompanied by the legendary keyboardist Bobby Emmons (at the 100-seat Bluebird Cafe, Nashville), reminded me of this interview I did with him in 1999. It was just prior to his show at the Auckland town hall concert chamber, with Spooner Oldham on a Wurlitzer electric piano. The show was intimate and spellbinding – and it was just the first half of a double bill with Jimmy Webb, plus Rick Bryant and Bill Lake as the support act. Sweet Inspiration, a compilation of songs by Penn and Oldham, covered by many soul, country and R&B greats, is about to be released on Ace.

He is such a mercurial presence in Southern music that he was also present, Zelig-like, at the creation of ‘I Never Loved a Man’, ‘When a Man Loves a Woman’ and ‘Suspicious Minds’. As historian Peter Guralnick puts it, the Penn is the “secret hero” of Southern soul.

Born in 1941, Penn is a pivotal member of the Memphis-Muscle Shoals gang that gave Stax a run for its money, and wooed characters as diverse as Bob Dylan and Cher down to Alabama to capture some of the magic. He was there when Arthur Alexander recorded ‘You Better Move On’ in Muscle Shoals, and started it all off; he talent spotted Percy Sledge; he was present when Aretha changed history with a few piano chords; he produced ‘The Letter’ for Alex Chilton and the Box Tops; and when Elvis decided to record in Memphis once more, he grabbed a camera to get in the door.

Penn, who plays New Zealand this month [March 1999] in a double bill with another songwriting legend, Jimmy Webb, was a Southern boy hooked on the R&B that came out of John R’s show on WLAC Nashville. He was so immersed in it that he claims he wasn’t aware of segregation when he was growing up: there just weren’t many blacks in his county, let alone the small town of Vernon (population 2000), where he lived beside a junk yard. “It was never an issue for the lot of us. I’m sure that the other side might have thought different.

“And when I was in my teens and early twenties, I was in the studio through all of that, and working with black people. So I didn’t know what the problem was! There was a lot of injustice down there,but there was also the same thing going on in New York City and Chicago. Everybody centres in on the South as the bad guy but they were no worse than a lot of the northern places at treating black people.”

“Conway was still pop then, rock’n’roll. I got him right before he went Nashville country. I made my first 700 bucks and bought me a car.”

Now Penn warms up. Legend has it he’s hard to get out from beneath a car to get songs written; both albums of his 45-year career (1973’s Nobody’s Fool and 1994’s Do Right Man) feature a shiny, curvy, classic Detroit beast.

“It was a ’54 Chevy, a four-door sedan with a ’56 V8 in it. It was a slick little devil, black. It looked like a school teacher, but in the back it had twin pipes. Of course I began to take all the chrome off of it and you could tell pretty soon it was a funky guy’s car.

It was in a ‘56 Caddy hearse that Penn’s singing career began. His band was called the Pallbearers and they played the drunken student frat-rock scene. “In Alabama all they wanted to hear was “Are you all right? Oh yeah! and ‘Bo Diddley’.”

Penn’s gritty voice reflected his idols: Ray Charles, James Brown and Bobby Bland. But when his songwriting took over, and with voices such as Arthur Alexander, Aretha, Otis Redding and Charlie Rich performing his songs, Penn’s own singing took a back seat.

“I got to singin’ on the demos, that was good enough for me. I got my licks in. I used them to sell the songs. I’m pretty sure that if it wasn’t for my singin’, I wouldn’t have got too many cuts.

“But you wasn’t going to get any white guys on black radio at that time. Even now, never. At that time it was kinda hard to get on the pop stations with sumpin’ real funky. We knew what the chances were of getting our blue-eyed soul on the radio. So that helped me stay in the studio and keep pitchin’.”

Penn says that his success with Conway Twitty was “a fluke”. It was when his friend Arthur Alexander had a hit with ‘You Better Move On’, recorded above a drugstore near Muscle Shoals, that Penn realised what could be achieved, despite their amateurism and their isolation. “My special memory of Arthur is that he got a hit. That was the beginning of believing for me. To actually see someone get a hit, someone I was hanging out with … I thought, mmm, I need to work harder.”

Shortly after, Alexander was having songs covered by the Beatles and Rolling Stones, though few royalties came back. “Arthur was an inspiration. I still have more respect for him than any other person I can think of in Alabama.”

But the person Penn regards as the “unsung hero” of Southern soul is Tom Stafford, who ran Fame Studios with Rick Hall: the tiny room above the drugstore in nearby Florence where musicians connected, took speed, and developed the Muscle Shoals sound. No one could have guessed that in a few years Jerry Wexler, the sophisticated New York producer for Atlantic Records, would bring Aretha Franklin down to Fame and change music history. Her career had been languishing at Columbia, but Penn knew her capabilities. He watched from the control room to see if some magic took place.

The song was ‘I Never Loved a Man’, nothing much from its demo. And it took a while for Aretha to click with the musicians. All white, they “walked and talked like sheriffs, and dressed like dollar-store managers off on a fishing trip”. That’s Robert Palmer ’s description; these Muscle Shoals cats grew up on country but lived and breathed R&B.

“I guess they’d been foolin’ round for about 20 minutes on that tune,” says Penn. “They played the demo, and everybody got the chords, and everybody was like, ‘But how we gonna start it?’ It was a little bit frustratin’. Ten, 20 minutes went by and it was coming to the place that everybody was looking at everybody.”

Until, that is, time came to record a

B-side. ‘Do Right Woman’ was written by Penn and Oldham, and Penn had just had time to lay down his guide vocal over a backing track when a fight broke out between Hall and Aretha’s husband. Next day, they fled back up north, the song recording incomplete.

“I was pretty well shattered. There just wasn’t anything there. I’m just squeakin’ a little on her key,and trying to carry the song through, and nobody’s made a committed effort to actually play the song. Just a little bass lick, a little drum lick … a little squeak on the organ and maybe a little guitar chink. There wasn’t really anything there, least, not to my ears at the time. But of course when I got to New York, she’d finished it off. And it was amazing.”

Penn moved up to Memphis to work with his friend Chips Moman and his great American Studios band. This was where they recorded the Box Tops, Dusty and, in his last great burst, Elvis Presley. “Chips’s style was just gettin’ in so tight with the musicians mentally. He was close to being one of ’em through the glass. The only flaw to his cuttin’ style was he took too many takes. He just cut ’em till their knuckles bled.”

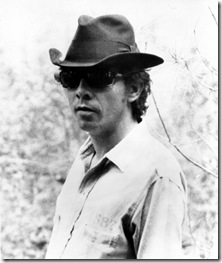

When Elvis entered the studio for what became the ‘In the Ghetto’ and ‘Suspicious Minds’ sessions, Penn had left American. “I just called over to take pitchers …”

You look even cooler than the man himself in one of them … “Ha ha ha. I had better glasses … I walked in, and they was playin’, and I thought it was great. But I was always hopin’ he’d return to ‘Don’t Be Cruel’. And further down the line, even funkier. Don’t get me wrong, I thought those records were great, but they were a little on the flowery side – and I still do. But I sure liked it better than ‘Blue Hawaii’.”

Penn just missed out on his Presley cut a few years later (“He was getting a little woozy then”) and to this day, the moment he cherishes most is James Carr’s version of ‘Dark End of the Street’. “Nobody has done it justice the way James did it. Aretha did it pretty good, and so did a lot of people. But James Carr was deeper than any of ’em. He had the voice. Put his on, and lean back, ’cause he’ll take you there. And that high-voiced girl singer in there? That’s yours truly. Ha ha ha.”

But who does Penn, the songwriter’s songwriter, regard as his mentors? “Oh, Lieber and Stoller, Burt Bacharach and Hal David. So many songs I don’t know the writers of but I know the songs. The great Motown writers. But now I have different mentors. Now I can definitely say that the Beatles were right up there with the best of ‘em, but at the time I rejected that, ‘cause it was so teeny weeny. As time’s gone along I’ve changed. I used to be, if it wasn’t black, I didn’t want to hear it. Now it doesn’t matter, I’m a lover of music.”

First published in Real Groove (New Zealand), March 1999.

5 comments:

Hi -- enjoyed the interview with Dan Penn. I have linked to it on my blog at http://soulfulmusic.blogspot.com/.

Thanks - and of course I should have mentioned that it was your blog that led me to the Bluebird cafe podcast. Cheers CB

First pic of Reggie Young I've seen. Thanks.

Glad I stumbled on this post - took me right back to that NZ tour. Their Wellington show remains as one of my all-time great concert experiences – possibly because I didn’t have too great an expectation heading in (similar to when John Hiatt tore it up as the “support” for Robert Cray a few years earlier). It was a rare treat and a privilege to see Penn and Spooner together.

Great interview and wonderful pics. Thanks.

Post a Comment